It already goes without saying: 2020 is like no other year. Across the globe we have hid in our homes for months. Social distancing has become an art form and an ideal, something to excel in, rather than the dubious expression of the lone hermit. As we gradually come into the ‘new’ normal we will surely start counting our losses, but there will also be time to reflect back. In this blog post I want to share some insights from our work on monitoring the pandemic through wastewater. In short, how to assess public health based on massive sampling and analysis of human shit. And what we can learn from this unusual spring.

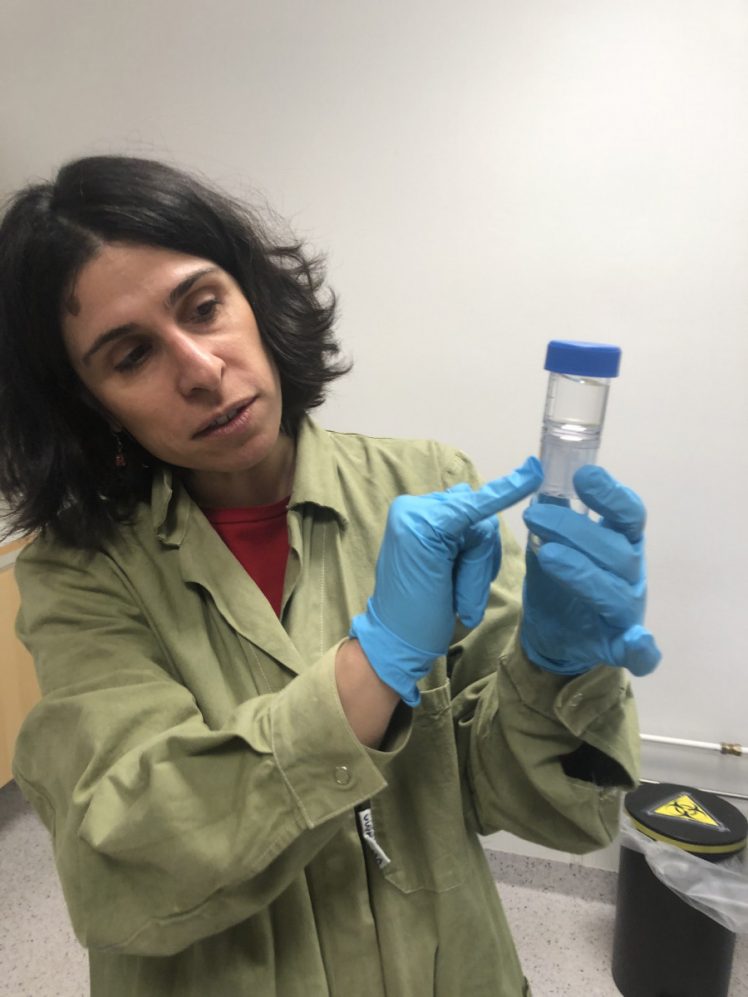

As the Corona virus started spreading globally in the beginning of the year, a number of Chinese scientists reported that the SARS-CoV-2, popularly known as “the new Corona virus”, could be found in patients’ stool (faeces). By March, preliminary results from the Netherlands showed that the virus could also be detected in wastewater. Following a webcast seminar on March 25, a group of researchers at KTH decided to quickly put together a team to try and do something similar: to monitor the COVID-19 pandemic through the wastewater in Stockholm. Within five days we had mobilised a core team of six researchers representing four different departments at KTH: Zeynep Cetecioglu Gurol from Chemical Engineering; Prosun Bhattacharya and Tahmidul Islam from SEED; Cecilia Williams from Protein Sciences and Anders Andersson from Gene Technology, plus myself from the WaterCentre. We were joined by staff from Stockholm Water and Waste Company, Värmdö municipality and Käppala Wastewater Treatment Plan.

The media caught wind of it when we started sampling wastewater in Stockholm by April 6. Via broadcasting and the press it spread in no time and a news article in Dagens Nyheter from mid-April got close to 200,000 clicks within a day. A few weeks later, when we released the first preliminary results concluding that indeed, we could detect Corona in Stockholm’s wastewater, there was more media hype, with reports in major TV news and radio shows. Even popular shows like P3 Morgonpasset took it up, with reporters giggling about poop in prime time. The shit had really hit the front page!

So what’s this research really about, and how can it generate such tremendous interest? In short, we sample wastewater from three Waste Water Treatment Plants (WWTP) which cover about 1.7 million people in the Stockholm region. Using so called qPCR technique we can measure the content of RNA (the genetic code) from the virus which gives a good indication of the virus prevalence in the whole population. The first advantage is that you can assess the overall public health situation without testing millions of people. Every day, millions of people are providing “test samples” through their faeces. So by analysing samples from only three sites, we will be able to assess the spread of the virus in the whole population in Stockholm. The second advantage is that it only takes a few hours for the wastewater to be transported from the toilet to our sampling point at the WWTP. Patient-based testing, on the contrary, can take weeks from infection to a positive test at the hospital. Therefore, Wastewater Based Epidemiology (WBE) can be used for early warning and a recent study at Yale has demonstrated that public health administrations can get at least a week’s notice using this method.

Of course there are many challenges and uncertainties still. As I am writing this, the KTH team is optimising our protocol for the analysis method which is necessary before moving to scale, and before we can actually make the kind of predictions which the Yale team did recently. The protocol has to be both specific and generic: it must be tailored for the type of sampling we are doing and for the available lab resources we have, at the same time it must be compatible with other researchers’ work, both nationally and internationally. Keeping up with the international developments in this area is virtually a full time job, as the frontline is advancing at a staggering pace. We also face a myriad of day-to-day challenges, like making scarce consumables last, juggling with over-burdened lab facilities and cold storage spaces, or just explaining to our colleagues what we are doing… So far this rapid response has been largely self-funded by the participating researchers, and PhD students, post-docs and senior staff are doing an amazing job, working over time on voluntary basis. Just because this has to be done. The pandemic is here now and we cannot wait for time consuming application processes.

So what can we learn already now from this unusual experience? First, social networks are key. The research community has the ability to rise to the challenge – we just put together a team and started working – but people have to know each other, at least a little. Having a WaterCentre actually had helped us building these contacts before the outbreak. Second, the current research financing structures are quite useless for crisis situations. With so much being locked into externally funded long-term programmes and projects there’s basically no flexibility to rapidly respond to a challenge like COVID , nor to seize opportunities as they arise. Again, the fact that we had some un-allocated funding within the WaterCentre made it possible to start working immediately. Third, this could be the dawn of a new more open innovation and research paradigm. Ever since the first releases of scientific reports – many from China – about the Corona virus the academic community has embraced openness and principles of sharing, for example of protocols. Using data-sharing hubs and initiatives at EU-level we see that we can advance knowledge at a much faster pace than if we each jealously protect our information.

After the pandemic, we are going to face other crises, induced by climate change, global economic re-structuring and geopolitical struggles. Hopefully we will retain at least some of this challenge-driven approach and our collaborative spirit. We are going to need it.