Driven by curiosity

Education

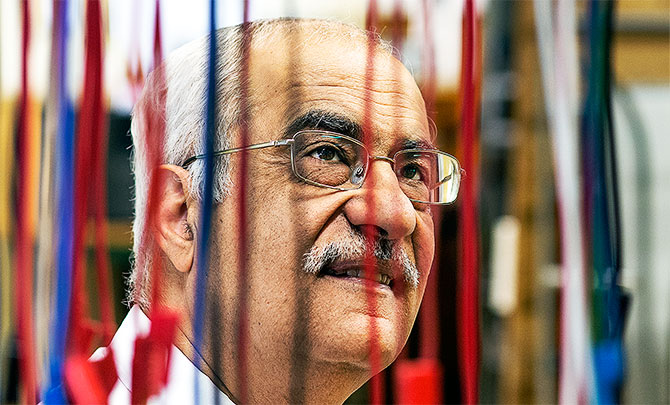

Professor Chandur Sadarangani has led major advances in his field, design engineering. When he retires next month from KTH Royal Institute of Technology School of Engineering, he leaves a legacy that spreads far beyond the lab and classroom.

Chandur Sadarangani knew early on that he wasn’t cut out for the family business. Born into an Indian family whose history in the clothing trade spanned generations, Sadarangani saw one sibling after another follow in their father’s footsteps, while he became increasingly absorbed in how machines function.

“If something broke down in the house, I would take it apart because I was interested in why,” he says. “I usually didn’t put it back together, but I was fascinated by how things work.”

When he retires in November 2013 from his position as Research Leader at Electrical Machines and Power Electronics, Sadarangani’s legacy will be evident in the increased efficiency and sustainability of countless power engines used in daily life, from manufacturing systems to hybrid automobiles.

His most important ideas were formed during Sadarangani’s 15 years in the private sector, first with Allmänna Svenska Elektriska Aktiebolaget (ASEA) in Västerås and then with ABB. But he’s quick to also give credit to a number of former PhD candidates, some of whom have leading positions in research and development with ABB as well as KTH. “I had great students,” he says.

The professor recounts his story in a soft-spoken manner that makes it easy to see why he may not have been suited to working in sales with the rest of his relatives. Sadarangani’s evolution as an important influence in design engineering began soon after his arrival from the UK, where he lived and worked for a brief period after receiving his Bachelor degree from the University of Manchester Institute of Science and Technology. During a summer holiday in Sweden he met his wife, Kerstin, from Gothenburg; and after some attempts to settle down in the UK, the couple moved to her hometown. Sadarangani was soon enrolled in the PhD programme at Chalmers University of Technology in Gothenburg.

“My professor took me on the condition that, first of all, I only spoke Swedish, and secondly, that I never addressed him with the formal ‘ni’,” he remembers with a laugh. After graduating from Chalmers, he was recruited as a design engineer for ASEA in 1979. “That’s where I learned a lot about electrical machines,” Sadarangani says. “After that, I was very solid.” Five years later, ASEA was absorbed by ABB and Sadarangani entered Corporate Research. Eventually he was awarded a Senior Scientist position in 1992.

His contributions include developing a U-shaped slot design for engine rotors, which has been patented by ABB. The shape reduces the parasitic effects of the converter, which is key to controlling speed. “Speed control of the motor is the way to win on efficiency,” Sadarangani says.

His transition to a professorship at KTH was natural. “I had a good background in industry and I found that with KTH, or a university, you could work with other companies,” he says. “What is most interesting is that you don’t work so closely to the product, so you are in a broader field of research.”

Upon arriva l at KTH, his presentation to the predecessor group of the School of Electrical Engineering teemed with a backlog of concepts he had wanted to explore while employed at ABB in Västerås. “I pursued those one by one,” he says.

As one of the founders of the Swedish Center of Excellence in Electrical Power Engineering at KTH, Sadarangani initiated KTH EE’s Permanent Magnet Drives programme in 1994. One of the projects undertaken was the development of highly efficient line-start permanent magnet motors used in pumps by water technology company Xylem.

In the area of hybrid vehicles, Sadarangani led the development of the free-piston generator, an energy-conversion device that integrates a combustion engine and electrical generator into a single unit. The hybrid research also led to work on a four-quadrant transducer (4QT), a novel system which consists of two combined radial-flux machines, one double-rotor machine and one conventional machine (stator).

The 4QT enables a hybrid vehicle’s internal combustion engine to operate at maximum efficiency in any driving conditions.

“We made a prototype for Volvo Buses, which has shown very promising results,” Sadarangani says, pointing out that despite some initial scepticism, his hybrid concepts have been embraced internationally.

“Suddenly, it’s being researched around the world,” he says. “I recently saw a presentation from Italy and it was exactly the same concept.”

“Industrial relevance” is the term Lennart Harnefors, Professor of Power Electronics at EE, uses to describe the research that Sadarangani pursued. A former PhD student of Sadarangani’s, Harnefors says that this relevance is the key to the professor’s effectiveness in attracting financing.

“His research has strengthened the electrical machines and drives industry in Sweden through new ideas and methods, as well as well-educated people,” Harnefors says. “Many jobs have been created as a result.”

Harnefors says the professor was also quick to embrace and support his student’s choice of research topic, even though it fell outside of Sadarangani’s personal areas of interest. “He was always very pleasant. Chandur’s career shows that you don’t need a big ego to be a great professor.”

By Sadarangani’s own account, the key to his success has always been his insatiable curiosity. And his journey isn’t over just because he is retiring. The professor will continue working as a consultant, and he’ll go on exploring his passion in his free time, as well.

“Electrical machines are used in so many applications; every time something new comes along, I must find out what’s new about it,” he says. “Every time I see something new that I don’t understand, I cannot resist the impulse to try to understand it.”