Urban waterways could reduce congestion

Urban Transport

For many cities, a solution for urban congestion might lie in one of the most ancient modes of transportation available – the boat.

Looking at how water-buses could be integrated into Stockholm’s mass transit system, researchers have a come up with a strong case for a maritime complement to trains and buses – and not just in Sweden.

Karl Garme, a researcher at KTH Royal Institute of Technology’s Department of Aeronautical and Vehicle Engineering, says the Waterway 365 project shows that water buses could reduce the load on land-based transit without doing harm to the environment.

In addition to adding capacity to a city’s transit system and changing transport flows, the researchers believe water transport could also create an opportunity to increase bicycle commuting volumes. It is easier to load bikes on and off of boats than buses, the report states.

“Boats should nevertheless contribute something, not compete with other parts of collective traffic,” Garme says.

The Waterway 365 report's aim was to show that waterways can be used to add sustainable transport capacity in urban systems, and to identify research questions and technical issues.

By teaming with Susanna Hall Kihl of Vattenbussen, the researchers transcended the engineering perspective of their subject and gained insights into market needs and community planners' challenges. “Susanna Hall Kihl has enabled us to put our expertise and knowledge in a clearer context,” Garme says.

A city comprised of islands, Stockholm seems a natural for the concept of water transit. Door-to-door travel time on at least one typical trip across town, the study shows, could potentially be reduced by one-third.

In order to gauge whether waterways can increase transport capacity in any city, Garme says five basic conditions have to be taken into account.

- The water buses have to be integrated with land infrastructure, physically and through payment systems.

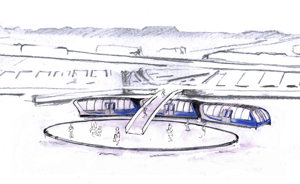

A water bus station - They should run year-round, even if the water freezes in the winter. The researchers point out that heavy steel reinforced hulls add to fuel consumption, but one solution could be that the system gets assistance ice breaking vessels that clear water routes, much as plow trucks keep roads open in the winter. “Our opinion is that lighter material can handle some ice, and we save fuel during the summer if we don’t need to carry around a heavy, steel-reinforced hull that isn’t needed then,” Garme says.

- Boarding and disembarking should be fast. “We want the boats works as a subway or a bus, where you get on and off from the sides, instead of at the bow or stern,” he says.

- That the boats are energy efficient, effective and efficiently produced. They also should be modular, with different sizes for different needs.

- Planning for water buses should be done before the possibilities are “built away”. Planning for water traffic has to be integrated into planning for the rest of the system or it won’t be profitable. “There’s also the risk that existing and potential berths might disappear because waterfront property is so attractive, says Hall Kihl.

Waterway 365 was conducted in collaboration with Vattenbussen AB, with support from the Swedish Maritime Administration.

All photos / illustrations, in addition to the photograph of Karl Garme, were done by Linnea Våglund and Karin Bodin.

For more information, contact Karl Garme at 070-397 1717 / garme@kth.se or Susanna Hall Kihl at 070-761 66 42 / susanna.kihl @ vattenbussen.se.

Peter Larsson/David Callahan

Read the Waterway 365 report