Engineered protein prevents dementia in mice carrying Alzheimer's genes

A newly-developed protein has successfully prevented dementia from occurring in lab mice carrying human Alzheimer's genes, raising the possibility for development of new treatments for the disease.

Hanna Lindberg, a researcher at KTH Royal Institute of Technology, worked with colleagues in Sweden and New York to develop a so-called binding protein that could target amyloid beta peptides, which are associated with Alzheimer's disease.

When equipped with the binding protein, the researchers found that laboratory mice carrying the genes for human Alzheimer's did not develop disease-related memory impairment or impaired cognitive ability, Lindberg says.

The proteins also prevented the occurrence of amyloid plaques on the brains of lab mice. These plaques result from the large-scale production of amyloid beta peptides in the brains of Alzheimer's patients.

"We greatly reduced the amounts of amyloid beta peptides in the brains of these mice," Lindberg says.

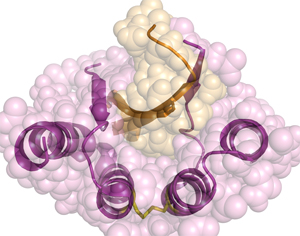

Binding proteins get their name from their ability to act as an agent in binding molecules together. These proteins mimic the function of antibodies but are much smaller. The proteins used by Lindberg and her team are based on affibodies — an engineered class of proteins that can be designed to bind tightly and specifically against various diseases' proteins.

"In our case, we have created lots of variations of the same binding protein to find the optimal version for the target peptides which are associated with Alzheimer's," Lindberg says.

So far, she says, the results are promising. "The mice that received the treatment with affibody molecules behave just like healthy animals when it comes to memory and cognitive ability," she says.

The test results could provide the basis for work on new treatments for Alzheimer's, Lindberg says, adding that a drug could be available within a decade if all the conditions are favorable.

"Alzheimer's is the most common dementia disease today," she says. "There are medicines for the symptoms, but no effective treatment method. The medications do not attack the fundamental disease mechanisms, and they tend to become inactive after a while."

According to the Alzheimer's Association, 35 million people suffer from Alzheimer's disease today, and this figure will triple by the year 2050. It usually develops slowly and gradually gets worse as brain function declines and brain cells eventually wither and die. Ultimately, Alzheimer's is fatal, and currently, there is no cure.

Stefan Ståhl, dean of the School of Biotechnology at KTH and a professor of molecular biotechnology, has been the main supervisor of Hanna Lindberg.

"I recently came home from a project meeting at New York University," Ståhl says. "It was clear to me that the results achieved by Hanna protein were so good that they are on par with other protein-based preventive medicines that have been used in clinical trials for Alzheimer's disease. In most cases, these are monoclonal antibodies. No such drugs are on the market today."

The research project was conducted in collaboration with Professor Thomas Wisniewski at New York University School of Medicine and Professor Torleif Härd at the Swedish University of Agricultural (SLU).

Peter Larsson/David Callahan

For more information, contact Hanna Lindberg at +46 8 - 55 37 83 38 eller hanli @ kth.se

Read the paper, Engineering of Affibody molecules targeting the Alzheimer’s-related amyloid β peptide