A revolutionary table turns 150

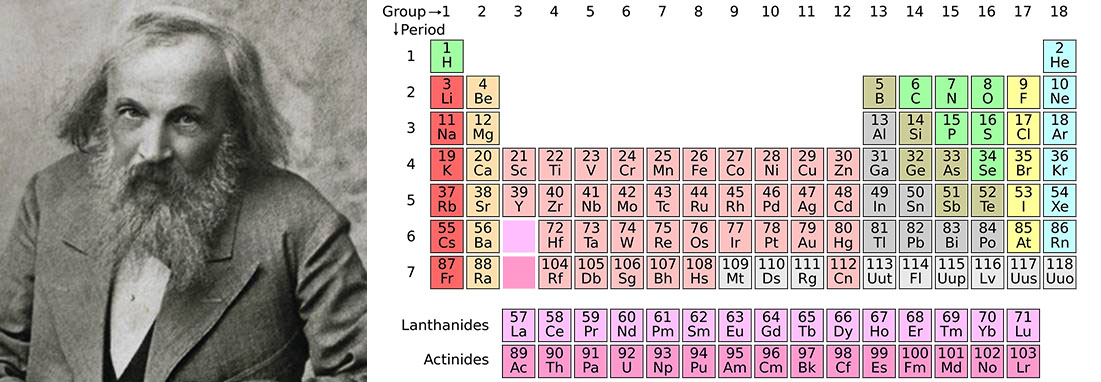

He invented the periodic table but never received a Nobel Prize. This year is the 150th anniversary of the periodic table of elements. And the periodic table still hasn’t finished growing.

Many of us have sat at a school desk slogging our way through the names, properties and position on the periodic table of the various elements. The periodic table is an ingenuous method for organising the elements based on atomic number (the number of protons in the nucleus of an atom), electron configuration and chemical properties.

This year sees the 150th anniversary of the invention of the first version of the periodic table by Russian chemist Dmitri Mendeleev, something that has been recognised by the United Nations General Assembly and UNESCO, who have proclaimed the International Year of the Periodic Table of Chemical Elements.

Perhaps not many of us have any use for the table in our daily lives; however, it is difficult to speculate what the world might look like without the periodic table, something that is essential to enterprises such as the development of new medicines, technologies and foodstuffs, explains Joakim Odqvist, associate professor at KTH:

“The periodic table is an important tool for both chemists and physicists, not to mention those working in the borderland between these two disciplines; for example, in my own field of materials science,” says Joakim, who works on the thermodynamic and kinetic modelling of alloys with industrial applications.

“Without the periodic table, it would be difficult to understand why certain elements tend to bind to others in a certain way, which in turn affects the material’s physical properties such as melting point, theoretical strength and surface energy.”

Joakim Odqvist explains that, although Mendeleev arranged the elements based on atomic weight, there was an initial lack of any deeper understanding of the underlying physics regarding why groupings appeared as they did.

“It was not until quantum mechanics enriched the field of atomic physics during the 1920s that we could understand why the elements had a given distribution of electrons and how this can be linked to their chemical properties.”

In 1869, Mendeleev’s system encompassed 63 elements but he understood the need to leave gaps for as yet undiscovered elements. At the time of writing, there are 118 elements on the periodic table and, in theory, more may turn up.

“New elements are discovered from time to time, although this now happens mostly in a laboratory environment. Researchers have been able to predict the likely existence of new elements. There does not appear to be any unequivocal answer as to whether it will be possible to identify or produce new elements indefinitely; however, it is clear that it is becoming increasingly difficult to make such discoveries. Most new elements produced are unstable; they are often radioactive and decay over time.”

Swedish researchers have been at the forefront over the years, discovering in the region of 18-21 elements, with oxygen, silicon, chlorine and tungsten among the best known.

The small town of Ytterby north of Stockholm is the place on Earth with most elements named after it. Nine elements have been discovered in the town’s mine, of which four are named after the location – ytterbium among them.

Despite Dmitri Mendeleev’s arrangement of elements being hailed as one of chemistry’s greatest discoveries, the Russian never won a Noble Prize. When the prize was established some 32 years after his table saw the light of day, it was deemed too far back in time.

Text: Anna Gullers