Electronic voting - easier, but risky

Special interest groups could gain inordinate power

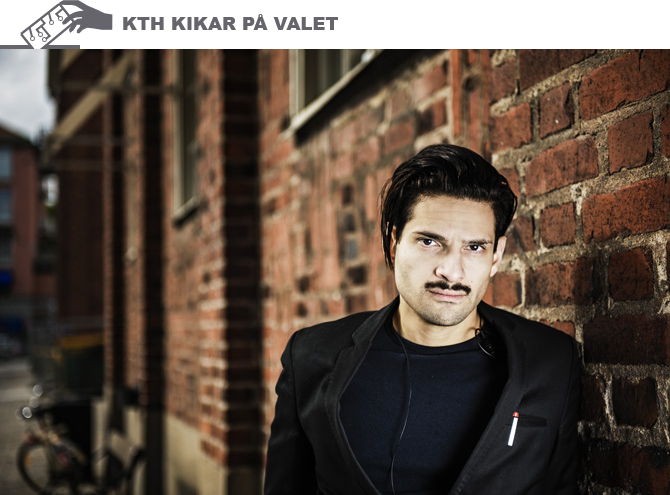

Easy – but risky for democracy. Electronic elections would increase pressure to implement more and more referenda. And that could be devastating to a country’s social structure, says philosophy researcher Karim Jebari.

The ability to vote electronically would simplify the voting process, which in itself is positive, says Jebari, whose research focuses on ethics and technology.

“Anything that lowers the threshold for voting is good,” he says. “If you could do it via the web, for example, more people would certainly participate – especially young people.

Jebari says he does not believe the argument that electronic voting would trivialize elections – that people would take them less seriously.

“Those who grew up with the ritual of going to the polling station would surely continue doing that; while younger voters would vote digitally with the same seriousness,” he says.

However he says that the simplicity of implementing electronic elections could also invite more referenda on a variety of issues.

And that’s a danger to democracy, Jebari says. Experience from states with referendum systems shows that the majority of voters cannot be bothered to engage in too many polls. The low voter turnout that results from “referendum fatigue” leaves room for relatively small numbers of voters who are organized around a special interest to push through their proposals.

“It would be dangerous if the politicians cannot accept responsibility for pushing through a policy they believe in, and instead allow a small portion of the electorate to assume that role through referenda,” he says.

California’s referendum system resulted in powerful interest groups pushing through a law requiring that any legislative effort to raise taxes must be carried by a two-thirds majority vote of both houses. Other referenda in the meantime have passed laws that are at odds with restriction, in order to strengthen the public contribution.

Such contradictions in funding have caused the state to run constant budget deficits.

A functioning democracy is based not only on people promoting their own interests but also on thinking of the greater good, Jebari notes. Direct democracy via referenda enables well-organized interest groups ample room for driving through their own agendas. Especially if the majority of people cannot manage to get involved in politics, he says.

“The risk is that we get dysfunctional societies when small groups with contradictory interests become powerful political forces,” he says.

But technology is not the stumbling block for higher turnout and a stronger democracy, he says. Rather, the issue is a social one.

“Democracy is the form of government that makes the strongest demands on its citizens.

“You have to be interested in politics, be able to understand the issues, and be able to see through the rhetoric of politicians,” Jebari says.

Christer Gummeson