NASA to use KTH technology to study solar impact on Earth

Space

When NASA launches four satellites next year to study the sun's impact on Earth's magnetic field, scientists will rely on engineering developed at KTH.

Instruments developed in part by KTH Royal Institute of Technology in Stockholm will be used by NASA in an ambitious space physics project involving four satellite launches in 2014.

The Magnetospheric Multi-Scale (MMS) project will help scientists understand the interaction between the sun and its surrounding planets, including Earth, by using the Earth’s magnetosphere as a laboratory to study the microphysics of magnetic reconnection - a fundamental plasma-physical process that converts magnetic energy into heat and the kinetic energy of charged particles.

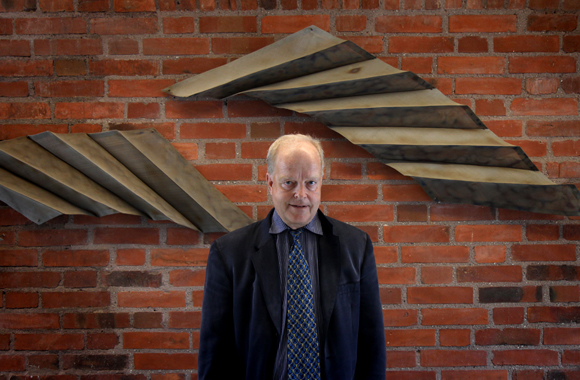

Göran Marklund, professor of Earth and Space Plasma Physics at KTH, says that magnetic reconnection is responsible for the aurora borealis and is also believed to be behind solar flares and other astrophysical phenomena.

The scientific investigation, Solving Magnetospheric Acceleration, Reconnection, and Turbulence (SMART), will contribute to solving problems on Earth caused by magnetic reconnection, Marklund says. “In connection with solar flares and space storms, the Earth's atmosphere is hit by intense particle flows.

“Not only do they generate intense auroras, they also knock out satellites, cause interference or interruptions in electricity supply networks, obstruct GPS navigation and radio waves, and generate strong ground currents that cause pipelines to rust faster,” he says.

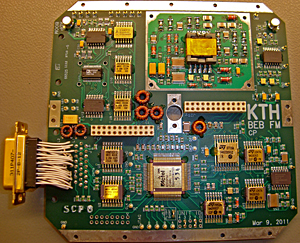

Each of the four satellites will carry probes with electronics and mechanics developed by KTH in collaboration with the Institute of Space Physics in Uppsala and the University of Oulu, Finland. Marklund says that KTH space and plasma physics engineers have been working at full speed on instrument construction, and delivery is now nearly complete.

KTH’s contribution includes a new mechanism for unfolding wire booms that extend the measurement probes far from the satellite body. A prototype was developed at KTH, and further developed and produced at the University of New Hampshire. KTH-developed probes are to be located at the end of each of the four 60-meter long wire booms on the four satellites.

“Our biggest contribution was to design all the electronics for the electric field experiments and the power supply for other scientific experiments,” Marklund says.

Marklund says that the equivalent of at least 10-years of work time has been dedicated to the project at KTH. After next year’s launch, and the instruments start taking measurements, research at KTH will be “very intense,” he says. “It will require at least as many years of engineering work,” he says.

NASA is responsible for building the satellites and the coordination of equipment, as well as coordinating the research mission, and analyzing and interpreting the data collected. Among the international team of scientists involved in the SMART investigation is Per-Arne Lindqvist, a space- and plasma-physics researcher from KTH.

The Swedish contribution to MMS is funded by external grants from the Swedish National Space Board, and faculty funding at KTH and the Institute of Space Physics, Uppsala.

For more information, contact Göran Marklund at +46 (0)8 - 790 76 95 or goranmar@kth.se.

Peter Larsson