New Helmet Technology Reduces Brain Injury

RESEARCH NEWS

It’s been about 15 years since neurosurgeon Hans von Holst decided he was tired of seeing so little done to reduce the severity of head injuries from sports or bicycle accidents that he saw in the emergency room at Stockholm’s Karolinska Hospital. He contacted KTH researcher Peter Halldin, beginning a collaboration that’s now on the verge of transforming EU standards for helmets.

“We never say that any other kind of helmet is bad. Helmets are lifesavers,” says Peter Halldin a professor in the KTH Division of Neuronic Engineering. “But the design of the traditional helmet hasn’t changed in 20 years. Our new MIPS helmet technology can save thousands more lives, and above all it can help avoid serious brain injuries.” Halldin and researcher Svein Kleiven worked with neurosurgeon Hans von Holst to develop the Multi-directional Impact Protection System helmet in the late 1990s.

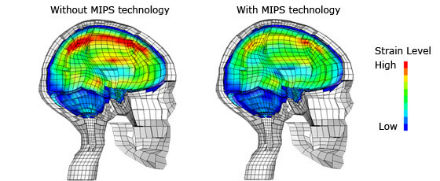

MIPS puts a plastic shield on the inside of the helmet — a casing designed to slide from side-to-side, absorbing collision impact and reducing the force of a blow to the head. The technology mimics the body’s own brain protection, where a cushion of cerebrospinal fluid slides in the cranium to shield the brain itself.

More than 60 cyclists and motorcyclists are killed in Sweden each year, while hundreds are severely injured. Head injuries are the most common and most serious consequences of bicycle accidents.

“Conventional helmets are designed to provide protection in a straight fall, but since most accidents involve impact from an oblique angle, the MIPS helmet is constructed to absorb energy regardless of direction,” Halldin says.

Oblique rotation injuries — the most common type caused by vehicle accidents — lead to about ten times more deformation of the brain tissue than a blow straight to the head. “I usually compare it to what happens to a boxer. It’s the rotation of the head from an opponent’s punch that causes the knock-out,” Kleiven adds.

The research team received a patent on the technology in 1998, and it’s now in use in riding, cycling and skiing. MIPSA, the company named for the technology, was founded in 2001. Prototype helmets have been produced for motorcycling and hockey.

“I want to MIPS technology to become a safety standard, just as airbags are now standard in cars,” Halldin says.

Helmet testing requirements currently in use call for dropping the protective straight down on a hard surface to test the strength of the external shell an the impact dampening effect of the cushioning liner.

“We have proposed a test method that would involve dropping the helmet on an inclined surface so there would be rotation in the blow,” Halldin says. “That would be a more realistic representation of an accident. The MIPS helmet reduces brain and neck injuries from rotation by as much as 40 per cent.

The first MIPS helmet, introduced in 2007, was about 25 percent more expensive than a conventional one. The price difference hasn’t changed significantly since. “Price isn’t a problem. But too few consumers are aware of this new technology. On the other hand, all the helmet manufacturers know about it,” says Peter Halldin.

Six manufacturers have so far adopted the MIPS technology. A new collaboration with the sports equipment manufacturer Scott has the express aim of creating ‘the world’s safest helmet,’ and Halldin says more partnerships are in the works.

“It’s really picking up steam now,” he says. “We want MIPS to be recognised as a mark of quality for helmets, where consumers will demand the "yellow dot" that we use to distinguish our products.”

MIPS is a member of the Swedish standards organisation SIS, and the company has representatives on the helmet committees of international standards bodies in Europe and the U.S.

Svein Kleiven, a researcher at the KTH School of Technology and Health, says that for each person who dies from an accidental head injury, as many as ten others suffer serious brain damage. “These kind of brain injuries can often cause personality changes,” Kleiven says. “I wonder why there isn’t a law requiring bicyclists to wear helmets, like the seat belt requirement in cars. Society has to pay the costs for all these lives being needlessly destroyed.”

Professor von Holst expects the regulations to change eventually. “Demand for MIPS technology is going to explode. We couldn’t have pushed through the change in helmet standards at the EU level if it hadn’t been for our interdisciplinary work between healthcare and technology.

The research team at the Division of Neuronics says MIPS development work will continue with simulations of injuries incurred in real accidents. Lobbying efforts also continue, promoting more advanced testing of helmets.

For more information: Peter Halldin, +46-739-85 00 61; peterh@kth.se.