Converting olive mash into cash

An experimental system to create heat and power with waste from olive oil processing is up-and-running in Spain. KTH's lead researcher on the project, Carina Lagergren, reports on this new way to reduce environmental damage and convert organic waste to energy.

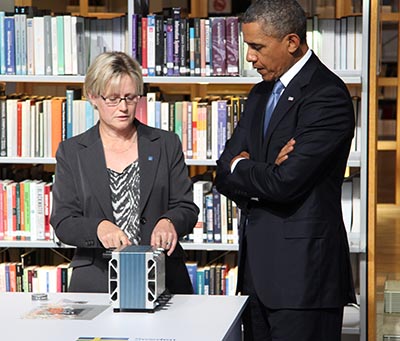

Fuel cell technology was the main attraction for the first-ever visit by a U.S. president to KTH in 2013, and one of the projects presented to President Barack Obama in the KTH library was a process to convert waste from olive oil production to energy for fuel cells.

The project reached its conclusion toward the end of 2014, and today a small-scale prototype system is fully-operational in an olive oil production facility operated by cooperative of San Isidro de Loja, Granada. The electricity it produces is used to help power the plant.

"I remember the President was very curious," recalls Carina Lagergren, the research leader in applied electrochemistry who presented the project concept to Obama. "He asked, 'If my friend — a farmer — wants to buy this system to produce electricity from waste on his farm, is it worth it?' And, I told him it's not, for the moment, because it's such a new thing. You cannot buy this and expect that you can save a lot of money."

"But in the future we hope it will," she says.

The system currently produces around 1kW of power, and the project partners — which included PowerCell Sweden AB — are planning to apply for funding to scale the operation up to create 200kW, or enough to supply 50 percent of the processing plant's energy needs, she says.

"But for this project, the most important thing was finding a solution for all of the toxic waste left over from olive oil production," she says.

Converting the waste to heat and power is a three-part process, beginning with a digester tank that breaks the material down and releases biogas, comprised of methane, carbon dioxide and sulfur compounds, to a reformer. The reformer converts the biogas into carbon dioxide and hydrogen, which can then be converted in the fuel cells. When oxygen is introduced in the cell, it mixes with the hydrogen and CO2 to create heat and electricity.

The process depletes the toxicity of the waste and what's left can safely be transferred to landfill.

"The idea behind the project is to show that it is possible to connect these processes together — starting with olive oil waste — and end up with electrical energy," she says.

Doing so is a much more sustainable alternative to the current process. After olives are milled and their oil is drawn, the waste containing pesticides and toxic organic compounds is dumped into sludge pits, where it introduces toxins to the surrounding environment.

So PowerCell, KTH and others joined forces to find a better way. For this project PowerCell called on KTH to analyze the influence of impurities of the biogas on their fuel cells.

"We fed the cells with the contaminants that are found in the fuel from the olive oil, or from the environment where the fuel cells operate, such as hydrogen sulfide and ammonia" Lagergren says.

The KTH researchers also looked into how the impurities affect the fuel cells. "Is it the electrode that suffers, or the electrolyte or the platinum itself, the carbon or the polymer?" she explains.

Lagergren says the answers will help the company define steps for cleaning the gas, and it also provides knowledge of the specifications of the fuel cells for those who are working with the technology.

While the technology is still costly for converting olive mash into cash, fuel cells in general offer a promising alternative source of electrical energy. Molten carbonate cells, for example, already are used for very large systems.

On KTH's end, Lagergren says the work toward a better fuel cell continues with a focus on bringing down the cost and increasing the efficiency. She is also involved in a project, with Lund and Chalmers universities, to find alternatives to the precious metals that are used as catalysts today in many kinds fuel cells.

"There are other ways to decrease the cost, such as work with the electrolytes. We try to do small improvements with the different components," she says.

David Callahan