At the risk of repeating myself (I wrote a similar blog just a few months ago), I felt it was important to return to this issue in light of the latest VR grant outcomes. The trends continue, and they demand our attention.

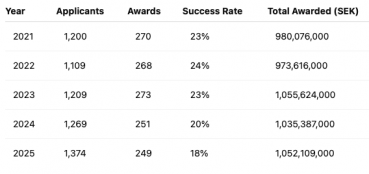

Here is the VR project grant data for Natural and Engineering Sciences (NT), 2021–2025:

The total funding has remained relatively stable. What’s changed is the number of applicants, up by nearly 200 in five years, and the resulting success rate, which has dropped steadily. This isn’t a case of declining quality, but of a system stretched too thin.

Rather than restating why fundamental, curiosity-driven research is important, a point that is, by now, broadly understood, I want to raise a different question: Are we simply too many researchers competing for the same pot of money?

My answer is no. The system doesn’t suffer from an excess of researchers, it suffers from structural misalignment. We are, rightly, growing our research capacity in strategic areas like AI, quantum technology, and nuclear energy, where special initiatives and targeted investments exist. But these researchers may also apply for general project grants, which means the competition in that shared pool intensifies, while the size of the pool remains largely unchanged.

This imbalance creates pressure not because the science is weaker or less relevant, but because the system hasn’t adapted to its own strategic expansions.

If we continue expanding our research ambitions without recalibrating the funding architecture, we risk cultivating frustration instead of innovation. Excellence is no longer enough, luck and timing increasingly decide who gets to move forward. This is a dangerous signal to send to our most ambitious minds, especially early-career researchers.

No comments yet. Be the first to comment!