Robots play music and dance in KTH opera

Published Nov 24, 2022

The two robots King and Queen have important parts to play in the final scene of The Tale of the Great Computing Machine, the opera which premieres at the KTH Reactor Hall on 1 December. One plays an interactive musical instrument, the Vocal Chorder, and the other dances and plays the Skandia cinema organ, which is housed in the Reactor Hall. Åsa Unander-Scharin, choreographer and one of the artistic directors, was assisted by KTH student Elsa Benzinger when programming the robots.

“The opera is about a society gradually being taken over by what we today would call AI. It’s a machine society. As the story unfolds the technologies become less and less dependent on humans,” says Unander-Scharin.

At the centre of the performance is Computa, a singing voice from a future where computers have taken over, something which also happens during the performance. She is played by court singer Anna Larsson, whose voice is pre-recorded.

“No one really knows where Computa is. She’s everywhere and nowhere,” says Unander-Scharin.

Several incarnations of Computa

Computa might for instance make herself known in the organ from Skandia cinema, which is housed in the Reactor Hall and is part of the performance. Or indeed in the form of the two robots, King and Queen, who turn up in the final scene.

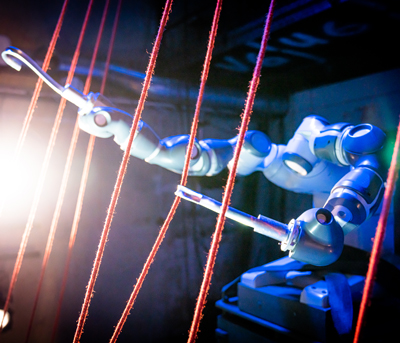

Queen plays the Vocal Chorder, an interactive musical instrument that Unander-Scharin and her husband Carl Unander-Scharin have been developing since 2004. The instrument consists of a series of long cords that extend up into the stage area’s ceiling. The cords play different sounds and notes when pulled.

“In the beginning it’s the humans who play the Vocal Chorder. But towards the end, when Computa has come to the conclusion that she cannot trust the humans, she instead plays herself in the form of the robot Queen, one of the many incarnations of Computa,” says Åsa Unander-Scharin.

A KTH student has programmed the robots

She choreographed the robots’ movements by pulling their arms into different positions. KTH student Elsa Benzinger then programmed the motion data into the software from ABB. The company, which is a strategic partner to KTH, has lent the two robots to KTH for the performance.

Benziger says that the actual programming was relatively simple.

“Åsa moves a robot arm into position, and then we tell the robot that this is the position it’s going to be in by saving the motion data in the program. We can then tell it to move to another position which we’ve saved,” she says.

However, getting Queen to play the Vocal Chorder was a challenge. In order to be able to play the instrument the robot has been programmed according to sheet music as well as to ensure it plays at the right time in the music. To accomplish this Unander-Scharin and Benzinger had to fine-tune the parameters speed and time – i.e. the speed of the robot’s movements, and the duration of each one.

“We settled on setting the robot to maximum speed, and then we instructed it via the software to make the movement in, say, five seconds. It then performed the movement at the required speed,” says Benzinger.

A challenge getting the robot to pull the ropes

Another challenge was that Queen, just like King, is a collaborative robot. It is designed to work with people in a factory and should not be able to harm them. There is therefore a limit on how much weight the robot can pull: around 500 grams.

The Vocal Chorder has something called balance blocks, which pull back the cords and make them heavier and heavier the farther they’re pulled.

“It’s a kind of dynamically altered resistance, which we have to fool the robot into managing, so we can find the right angle in the pull so that it uses the robot muscles efficiently,” says Unander-Scharin.

The robot King dances and plays the organ

Choreographing and programming King, the other robot, was simpler. He performs a sequence of dance movements and plays the cinema organ, the latter using a pair of rings called WaveRings.

“The signals from the Waverings are being transmitted to a receiver which receives motion data. A program, developed by music programmer Federico Visi, turns the data into MIDI (a protocol for sharing information between electronic musical instruments and computers, Ed.)which in turn chooses how the organ should play,” says Unander-Scharin.

Elsa Benzinger has also programmed King’s movements. She is currently in her final year of the masters programme in Computer Science at KTH. She programmed the robots within the framework of the Individual Course in Media Technology. During the rehearsal and performance period, she manages the robots. For this purpose, she is employed by Vadstena-Akademien, who produces the opera in collaboration with KTH.

“They have to be switched on and perform their sequence at the end of the show, so my job is to switch them on at the right moment. Before each show, I also have to make sure they’re working and are in their starting positions,” says Benzinger.

The opera The Tale of the Great Computing Machine runs 1–16 December 2022 at the KTH Reactor Hall.

Håkan Soold