The rise and fall of the Nord Stream pipeline: a brief history (part 2: the fall) 🧵

In summer 2011 laying of the first Nord Stream 1 pipe was completed. Italian pipe-laying vessels did the job. The second of the two Nord Stream 1 pipes followed a year later.

After Nord Stream 1’s inauguration the debate about it lost momentum for some time. The pipeline apparently operated smoothly.

The debate resurfaced in June 2015, when Gazprom and five European energy companies announced their agreement to build Nord Stream 2. The deal was very controversial due to Russia’s 2014 annexation of Crimea and support to separatist military forces in Donetsk and Luhansk.

A bad omen for the future came in early November 2015, when an unmanned underwater vehicle was found on the Baltic Sea floor, off the Swedish island of Öland, just next to one of the two Nord Stream I pipes. It was loaded with explosives.

The Swedish Armed Forces later confirmed that it was a Swedish military vehicle. It had gone astray during a military exercise held elsewhere in the Baltic Sea several months earlier. This was in the midst of the European refugee crisis and the event didn’t make many headlines.

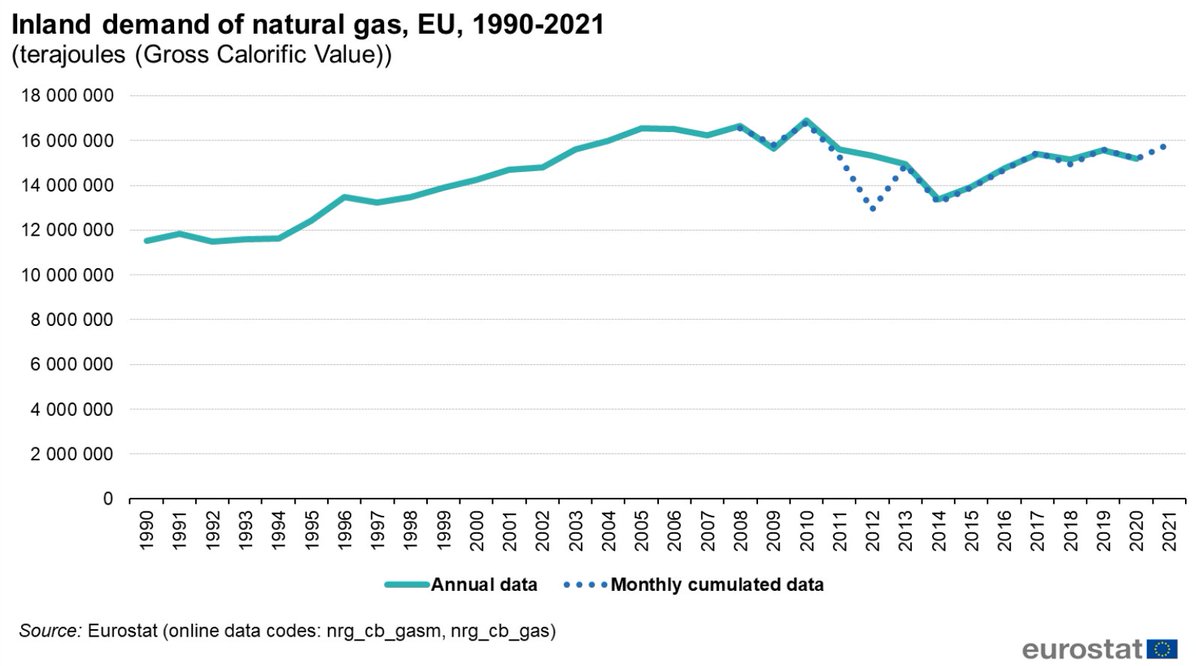

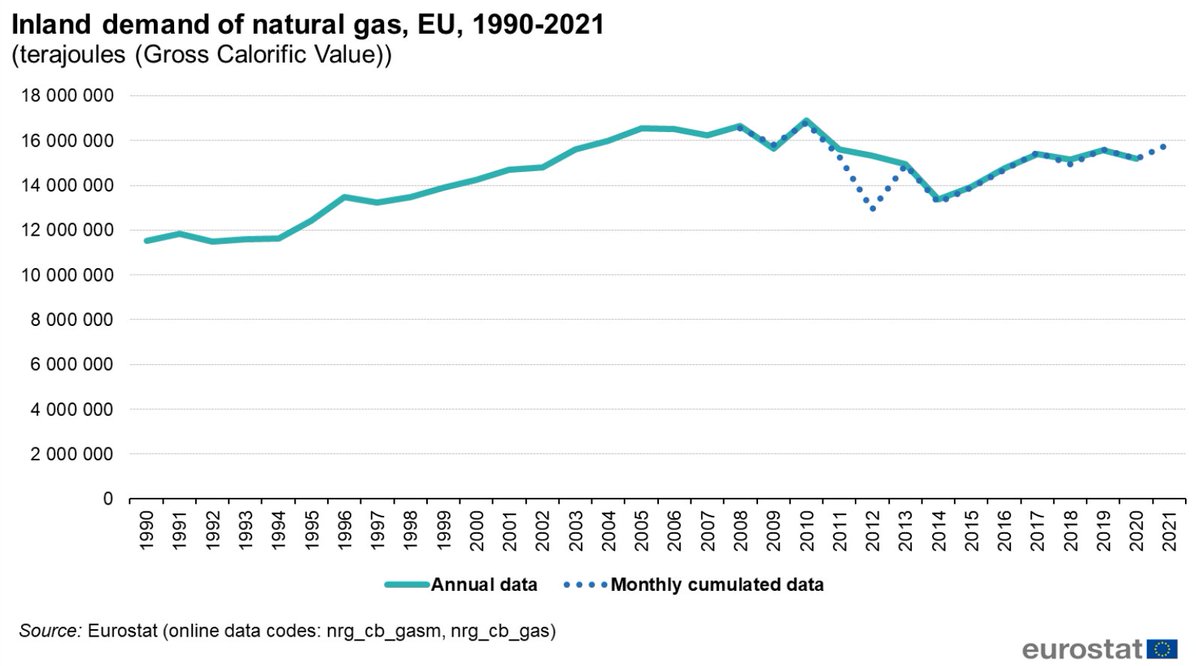

There was a fierce debate about whether Nord Stream 2 was actually needed. Critics noted EU gas demand, after half a century of rapid growth, had reached a plateau level and even seemed to be set for decline. No future growth in demand was expected. So why build a new pipeline?

Proponents of Nord Stream countered by pointing out that natural gas had a key role to play in the European energy transition: Russian or not, natural gas was a flexible source of electricity that could compensate for irregularities in wind and solar electricity production.

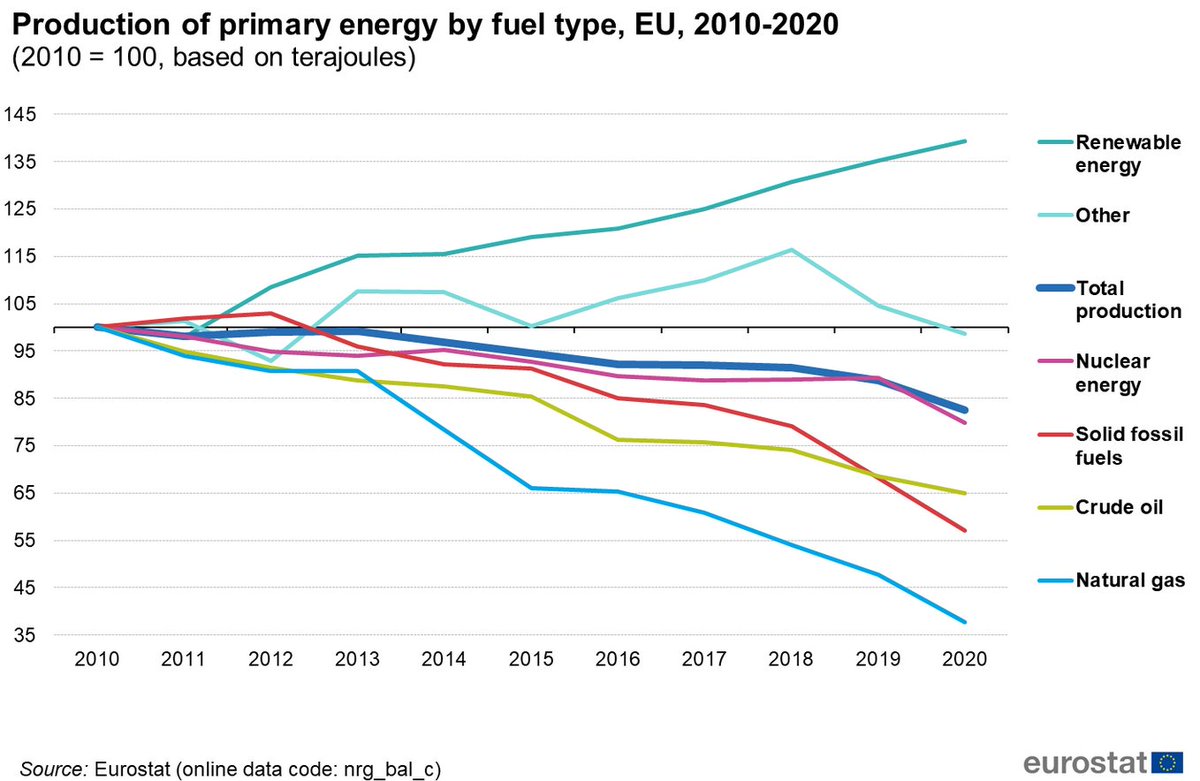

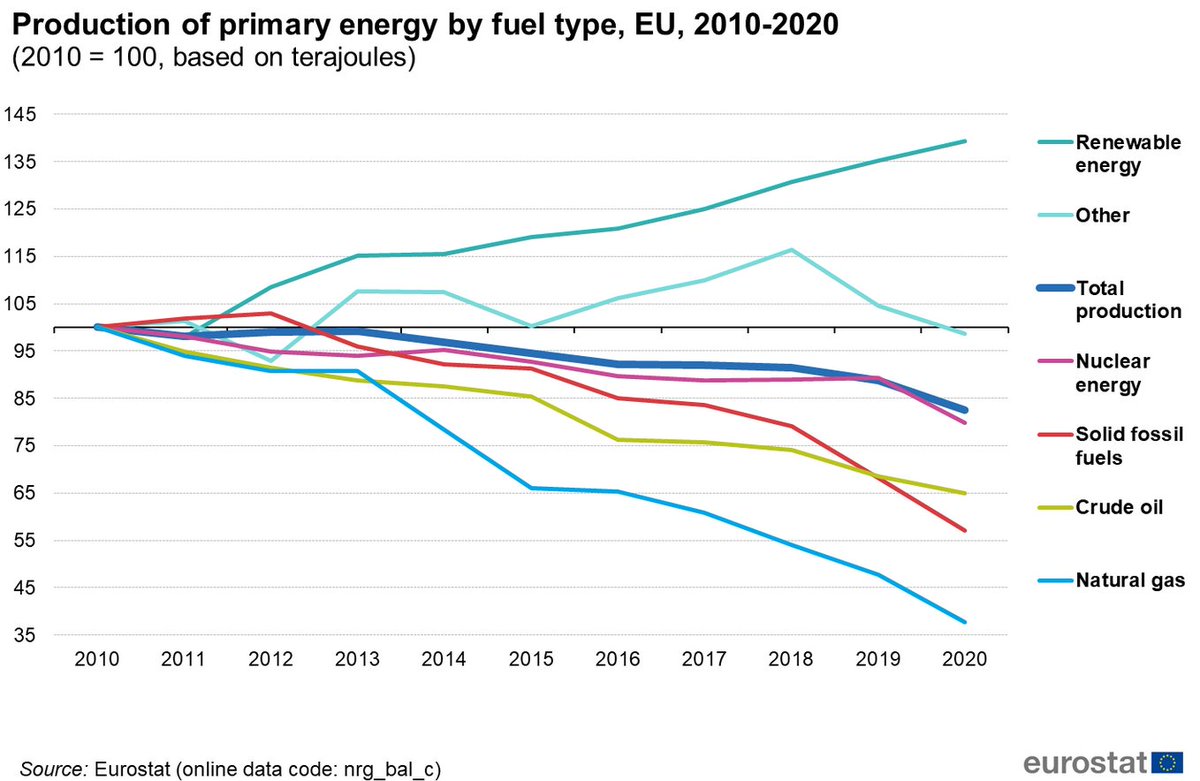

Proponents of Nord Stream 2 also pointed to another critical trend: internal West European gas production was declining helplessly, especially in the Netherlands. Internal EU production collapsed during the 2010s, falling by nearly two-thirds (!). Who would cover the deficit?

The EU Commission’s answer was: “Let the market decide!” Since Russia offered the cheapest gas, its exports increased massively in the increasingly liberalized EU gas market. Russia’s share of EU imports climbed from 31% in 2010 to 40% in 2016 and then stayed on that level.

Over time, this growing Russian dominance made EU agencies and national governments increasingly suspicious (while gas companies remained happy). The EU commission changed its mind about Nord Stream 2.

There were also critics on the other side of the Atlantic. Already the Obama administration lobbied against Nord Stream 2. This served two purposes: preventing Russian geopolitical influence in NATO member states and boosting US shale gas exports to Europe.

In the meantime preparations for laying Nord Stream 2 started. Several Swedish coastal municipalities wished to become involved in the project logistics. The Swedish Foreign Ministry sought to prevent them, but in vain.

Starting in October 2017, 52,000 Nord Stream 2 pipes were brought to the port of Karlshamn in southern Sweden, for temporary storage. This meant a welcome additional source of income for the Swedes. In 2018 the pipes started to be lowered into the Baltic Sea.

Then, Donald Trump stepped up the drama by imposing sanctions on companies that were involved in planning and constructing Nord Stream 2.

in December 2019 Allseas, a pipelaying company contracted by Nord Stream 2, gave in to US pressure. It abandoned the project, pulled out its vessel and moved it to Kristiansand in southern Norway.

This could not stop the project. It merely delayed it. Nord Stream 2 contracted a Russian pipelaying vessel and completed construction in September 2021. An intense struggle followed: should the pipeline be allowed to become operational or not?

Completion of Nord Stream 2 coincided with federal elections in Germany, which brought to power not only the Social Democrats, but also the Liberals and the Greens, which were much more critical to Russian gas than Angela Merkel’s resigning government.

The decisive blow to the project came with Germany’s decision to suspend certification of the pipeline on 22 February 2022, as a punishment on Russia for recognizing Donetsk and Luhansk as independent republics.

Two days later, Russia launched a full-scale military assault on the rest of Ukraine, including Kiev. Nord Stream 2 filed for bankruptcy already on 1 March 2022.

In June the gas flows along Nord Stream 1 were reduced by 60% “due to renovation work” and in July it was totally shut down for maintenance. EU governments started to prepare for a winter without Russian gas.

A turbine from one of the compressor stations was sent to Canada for technical overhaul, enabled by an exception from the sanctions. After 10 days this turbine was back in operation and the gas flow resumed, though only at the previous 40% level.

A week later the flow was reduced again to a mere 20% due to “technical problems” with one of the turbines. Shortly afterwards, on 31 August, the pipeline was fully closed due to “repair works” and more “technical problems” (Gazprom cited an oil leak in one of the turbines).

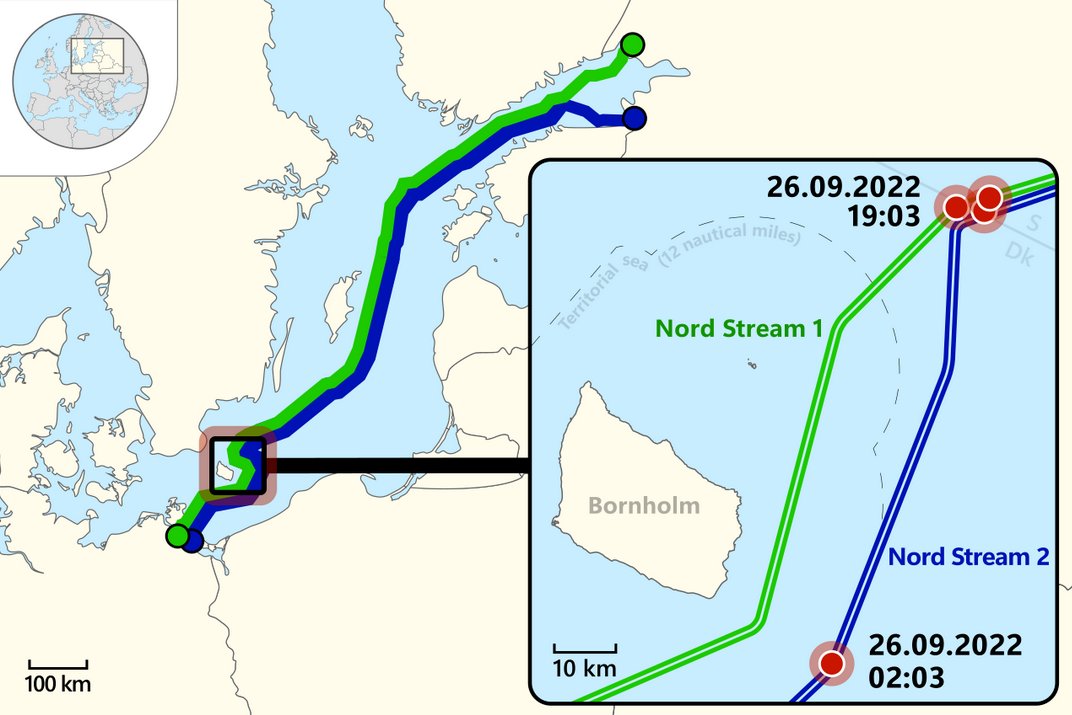

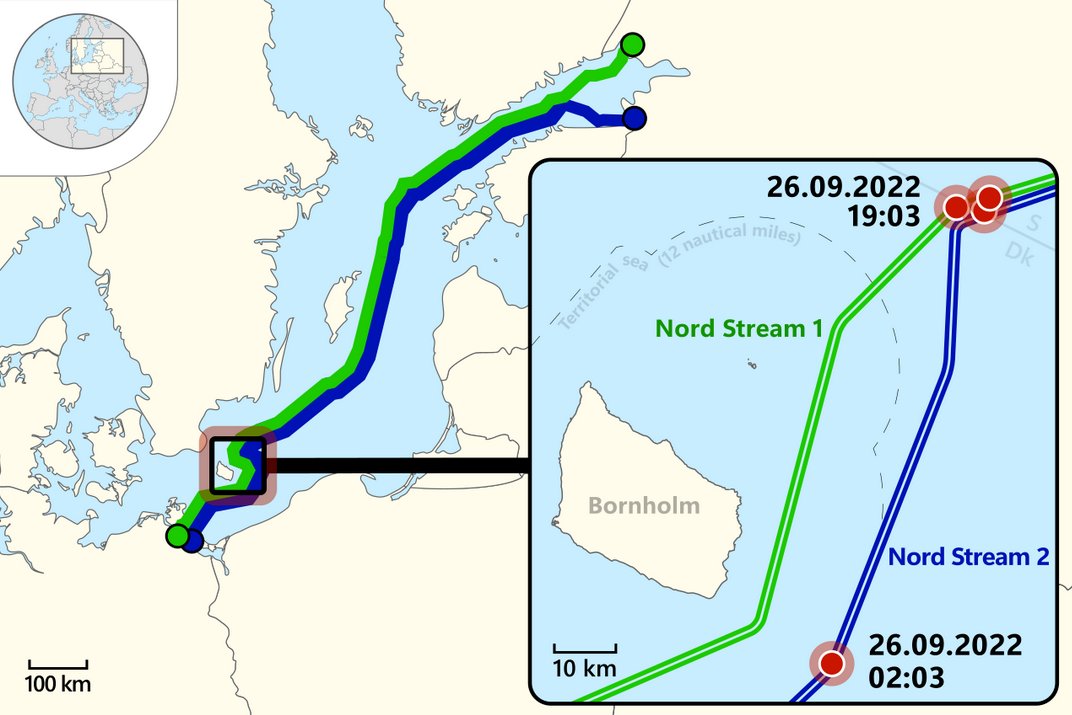

Then, on 26 September, several leaks in all four subsea pipelines were found in the Danish and Swedish economic zones. It quickly became clear that it was a result of violent sabotage. It remains to be seen whether Nord Stream 1 and 2 will ever go into operation again.

• • •

No comments yet. Be the first to comment!