Dr. Louis Delannoy is a Researcher for the Global Economic Dynamics and the Biosphere programme (GEDB) of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences, and the Stockholm Resilience Centre. A transdisciplinary researcher, Louis combines various tools to understand how crises are transferred, absorbed and linked across space, time and sectors of society. He specifically focuses on the conceptualisation and formalisation of polycrisis, and the development of a long-term multi-scale database on historical shocks and crises.

“Polycrisis” has become a buzzword to describe today’s overlapping challenges – from COVID-19 and the war in Ukraine to climate extremes and social turmoil. The intuition is clear: crises no longer come one at a time, but interact and mostly amplify each other. Yet the term is often used without precision. What does polycrisis really mean, how can we study it, and what does it imply for governance? At the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences and the Stockholm Resilience Centre, our team is working to answer these questions. In my seminar, I present three strands of our research: (I) a conceptual framework for polycrisis, (II) a global database of crises across five decades, and (III) an analysis of how institutions perceive risks compared to how they actually unfold.

First, it is crucial to understand what we mean by “crisis”. According to our social-ecological systems approach, a crisis emerges from two interrelated processes: shocks (diseases outbreaks, terrorist attacks, droughts, etc.) and creeping changes (democratic backsliding, biodiversity loss, etc.). The latter are considered much slower than the former, yet they must be regarded as critical. For example, intergenerational inequalities (which, when measured in terms of exposure to extreme weather events, have been steadily increasing since 1980 and are expected to worsen over time) are considered one of the factors contributing to Trump’s return to power. A polycrisis emerges when several crises overlap and reinforce one another. For example, when a heatwave worsens food insecurity or when a pandemic exposes long-standing weaknesses in health systems and social inequities. However, and as we found out in our first study, several interpretations of polycrisis co-exist. Yet if they disagreed on causes, they agreed on two points: polycrisis spans multiple scales, and it is more than a buzzword.

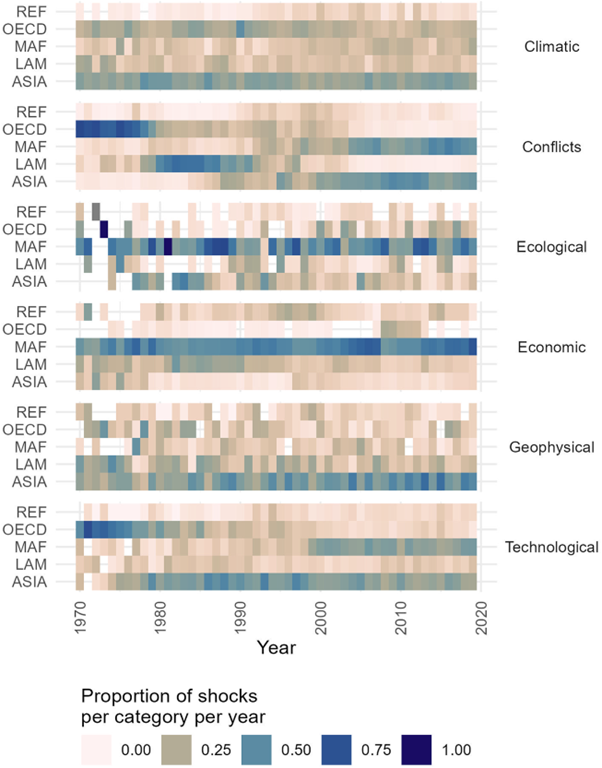

To see how polycrisis unfolds in practice, we built a database of shocks in 175 countries between 1970 and 2019. It tracks six types of disruptions – climate, conflict, economic, ecological, geophysical, and technological – year by year. The results show that shocks became increasingly entangled until around 2000, with combinations like climate–conflict–technology especially frequent. After that, patterns diverged by region: Asia experienced rising co-occurrences, while other regions plateaued or declined.

Figure 1 – The share of shocks per category per year in each region. REF = the reforming economies of Eastern Europe and the former Soviet Union, OECD = the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development 90 countries and the European Union member states and candidates, MAF = the Middle East and Africa, LAM = Latin America and the Caribbean, ASIA = Asian countries except the Middle East, Japan, and the former Soviet Union states. Source: Delannoy et al. (2025).

To complement this effort, we are conducting an expert elicitation process mapping creeping changes. The overarching goal consists in mapping where and when crises take place in the world, and what kind of interactions can we measure through empirical studies. A critical caveat is of course the inclusion in the process of several perspectives, especially from marginalized communities, often disproportionately affected by crises. Another caveat is the recognition of the risks of misinterpretation in how we conceptualize crises and communicate our findings, and our responsibility in this regard.

To bridge the gap with governance, we looked at how global institutions perceive risks, focusing on the World Economic Forum’s Global Risks Reports. These reports heavily emphasize economic risks, while downplaying ecological and long-term systemic ones. Additionally, they frame risks as complex, regulatory challenges rather than opportunities for systemic transformations. This creates a dangerous gap, where governance can end up preparing for the wrong risks while overlooking the creeping changes that quietly erode resilience.

Taken together, our work shows three things. First, polycrisis is best understood as the interplay of shocks and creeping changes. Second, history reveals recurring patterns of how crises cluster and diverge across regions. Third, governance often misjudges these dynamics, focusing on the visible while neglecting the systemic. Polycrisis is not just a buzzword. It is a call to rethink how we study, anticipate, and govern crises in the Anthropocene. By combining conceptual clarity, long-term data, and critical analysis of risk perceptions, we can begin to build the foundations for more resilient responses.

No comments yet. Be the first to comment!