New water innovations are needed to secure freshwater supply for human use, even in the Nordics that are typically perceived as water secure nations. Cryo-desalination, also known as freeze-melt desalination or freeze-thaw desalination, allows to obtain fresh water by freezing seawater. Is that even possible, how energy efficient is it and why is it not implemented yet?

New water innovations are needed to secure freshwater supply for human use, even in the Nordics that are typically perceived as water secure nations. Cryo-desalination, also known as freeze-melt desalination or freeze-thaw desalination, allows to obtain fresh water by freezing seawater. Is that even possible, how energy efficient is it and why is it not implemented yet?

In pursuit of new methods to obtain freshwater

Global availability of clean water is one of the Sustainable Development Goals set by the United Nations for 2030. The rise of global temperatures due to climate change is a major problem impacting every continent and threatening the ability to secure SDG 6. In many parts of the world the water footprint has already exceeded sustainable levels, whereas due to the global dimension of water consumption, many countries have significant impact on water consumption and pollution elsewhere. Looking into the future, it is important to think creatively about the types of innovations that will form tomorrow’s toolbox for securing not only water but also the health of ecosystems. Desalination is a very attractive nature inspired solution for obtaining fresh water from the seawater, which comprises 97% of the water in the world and yet has a marginal role in human water consumption. Traditional desalination processes (e.g. thermal evaporation, membrane processes) despite having improved performance over the years, they still lack sustainability and have systemic problems (e.g. linked to pollutants and membrane fouling).

The sustainability potential of cryo-desalination as opposed to traditional desalination is higher if we consider energy demand over the entire process. As the melting of ice takes approximately 7 times less energy than boiling water, cryo-desalination has the potential to be more energy efficient. In addition, since this approach does not rely on any filters in it can be fully sustainable form the perspective of new materials usage as well.

What is cryo-desalination?

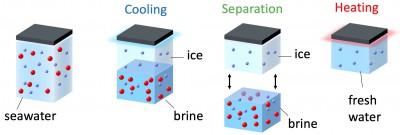

Cryo-desalination, the separation of water and salt upon freezing, utilizes the natural tendency of water to push out salt upon freezing. In practice, one utilizes energy to cool water and form ice. As ice is forming it expels most of the salt, resulting to the so called brine, which is very highly concentrated saltwater. Then the ice and brine are separated followed by the warming up of the remaining ice in order to obtain the fresh water.

Most of the energy required for the freezing and melting of ice can be recovered by an external thermal bath and coupling to a process that has excess cold energy such as liquid natural gas. Thereby, this technology can be applied equally to both cold and warm climates. The ice-brine separation is the critical step that defines the amount of seawater that can be obtained. There is a difficulty here though since during freezing salt and water mix down to microscopic level forming small brine pockets inside the ice. Understanding the water-salt separation mechanism could therefore be an important part of creating better technological solutions for cryo-desalination.

From water molecules to societal mainstreaming

There is no doubt that cryo-desalination is an expanding field of innovation with potential to address challenges of water insecurity. Nevertheless, few initiatives bridge this fundamental understanding of water with implications of the technology for market and societal mainstreaming.

Importantly, we find that a more broadly defined interdisciplinary approach could be beneficial for advancing cryo-desalination. It could for example combine basic research at the molecular level, with engineering and the social sciences, and thereby attempt to explore new connections across different fields of knowledge, with water as the common element. How might a molecular study of water become combined with insights from a social study of key water players in a growing city such as Stockholm to deepen insights about its feasibility?

A combination of field observations and interviews with water experts, energy and water utility companies but also business actors could provide a better insight into whether decisions about future investments in different water innovation portfolios can include more radical solutions. We know that insights from basic research such as from theoretical physics are crucial for solving complex water questions at the molecular level, but how could we further couple these investigations with other important fields of study?

Creating a safe space for new partnerships

Entering the recent Skolar Award competition which took place in Finland has been an incentive to push ourselves to think outside the box.

As water researchers ourselves (from theoretical physics and the social sciences), we have entered what might at times feel like an uncomfortable partnership. Because of the distance, we sometimes feel between our own disciplines. Moving forward however, we are excited to explore how this new partnership around cryo-desalination could provide a platform for asking a different set of questions around water that joins insights from molecular and societal perspectives.

Foivos Perakis

Assistant Professor at Stockholm University.

Timos Kaprouzoglou

Researcher, Division of History, Science, Technology and Environment, KTH.

Research coordinator of the WaterCentre@KTH.