A sticky solution to broken bones

Soon, you might be able to mend bone fractures with glue. At Greenhouse Labs on KTH Campus, KTH spinoff Biomedical Bonding is developing a new solution: an adhesive to fix complex bone fractures. KTH Professor Michael Malkoch explains how it works.

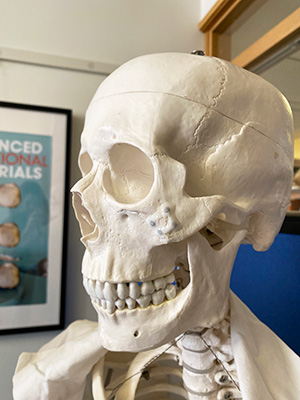

If you suffer a complicated fracture and need surgery, your surgeon often has to use metal plates and screws to stabilize the break. However, metal plates come in standard sizes and might not fit you. Additionally, during healing your body tries to encapsulate the foreign material. As a result, many patients need multiple surgeries and long recovery times before their fractures fully heal.

“In 2019, 180 million fractures were recorded, which corresponds to about six cases per second,” says Michael Malkoch. “If it’s a simple fracture, things usually go very well – you get a cast, and if you're young, you’re healed within 12 weeks. But if you're older and perhaps have osteoporosis, then standard treatments like metal plates and screws aren’t the best solution. Every individual is unique, and fractures can be very complex.”

Developing a glue for complex fractures

Based on his research, Malkoch is developing an alternative solution – a type of adhesive that can be used to fix complex bone fractures. Through the spin-off company Biomedical Bonding, he and his team are working to bring the technology to the market.

The material is currently being tested in veterinary medicine, but the goal is to secure funding for clinical trials in humans.

“Our plan is for the first human clinical trial to focus on finger fractures, which often come with many complications and are costly for society and healthcare systems.”

How it works

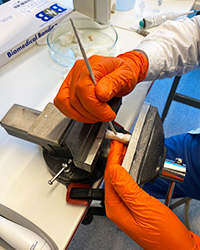

“We use a technique based on something called thiol-ene chemistry,” says Malkoch. “It’s a very selective chemical reaction where molecules don’t react until they are exposed to an external activation source – in our case, blue light.”

The technique is not only precise but also gentle. Since blue light is already used routinely in dentistry – such as in curing dental fillings – it is already known to be tissue-friendly.

The surgeon simply mixes the material and applies the adhesive directly to the fracture. It can also be combined with screws. Once the surgeon is satisfied with the shaping, the adhesive is hardened using blue light.

“The material is viscous, like liquid honey. The advantage is that the surgeon can fully customize the implant to the patient’s needs. We've also observed that the body doesn't treat our material as foreign in the same way it does with metal implants – it doesn’t try to encapsulate it.”

Research doesn't have to end at results

Michael Malkoch has led several commercialization projects with support from KTH Innovation and has founded multiple companies during his time as a researcher at KTH – including the publicly traded Polymer Factory. His entrepreneurial spirit was sparked after a stay in the United States.

“I realized that research didn’t have to end at results – it could also be pushed further toward patentable outcomes, and beyond. Whenever I see the potential to patent a result, I get in touch right away.”

Through KTH Innovation, Malkoch has secured funding, gained access to networks, and also traveled to Boston with the Brighter Program.

Next year, Malkoch hopes that Biomedical Bonding's products will be available on the market.

“The next step is to secure investment for clinical trials in humans. Our big vision is to establish the next medtech company in orthopedics – a Swedish company that can contribute innovative alternatives to outdated technology.”

More information

Contact: malkoch@kth.se

Text: Lisa Bäckman