We tend to associate nuclear power plants with many different things: smoking cooling towers, Homer Simpson-like operators, or dramatic TV series like HBO’s Chernobyl. But something people generally do not associate nuclear power plants with are massive amounts of water. Still, water is at the centre of nuclear power’s historical development, contemporary challenges, and further future.

The connection between water and generating nuclear power goes back to the Industrial Revolution, when steam technologies such as boilers and steam generators were used to heat up water, turn that water into steam, and use the energy of that steam to generate power. However, this led to many steam explosions with deadly casualties. Countries like the U.S., France and Sweden enforced safety rules, which stipulated how the boilers had to be designed and what the allowed pressures and temperatures were.

In the 1950s, more and more countries saw the potential of using nuclear technologies to generate power. With its Atoms for Peace-program, the U.S. took the lead and promoted the reactor type they developed: the light water reactor. This reactor type uses normal water as a coolant and had its origins in both naval propulsion and fossil fuel power generation. This continuity thus made water-cooled reactors a relatively simple way of rolling out nuclear power fast.

The safety in nuclear power plants was therefore determined by the control of water and the understanding of thermal-hydraulic phenomena, such as transients and steam explosions. The pressure vessels, steam generators, valves, pipes, tubes, and pumps of nuclear power plants suddenly became subjected to the steam regulations of the Industrial age. This created new risks since these codes and regulations did not consider radiation. One of the codes that underwent revision was the Boiler and Pressure Vessel Code of the American Society of Mechanical Engineers (ASME). The Code started travelling and was, for instance, almost directly implemented in all Swedish nuclear power plants. Gradually but surely, nuclear safety regulations in the West became more ‘nuclear’ as the intersection between water, steam, steel, and radiation became better understood and nuclear accidents, such as Three Mile Island, pushed governments for more safety legislation.

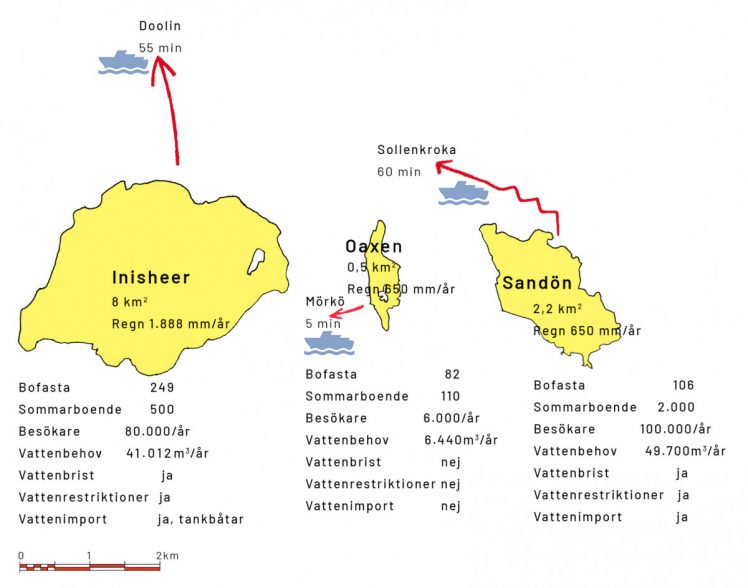

For the USSR water was equally crucial along all steps of the nuclear lifespan, such as mining, fuel element production, exploitation, and the storage of spent nuclear fuel and radioactive waste. In general, all nuclear power plants were placed next to either a river, a lake or the coast – the latter being an exception. The most common source of coolant was river water. Interestingly, those rivers usually had to be previously ameliorated and often artificial water reservoirs were created.

A specific setup was used for so-called energy complexes, a special form of nuclear-hydrotechnical combine. They embodied the combination of nuclear and hydro power, agricultural irrigation, and fish cultivation in one location. Furthermore, constructing them meant to manipulate water bodies with newly created dams. In this way an energy complex was created to procure valuable synergies through the multiple usage and partial recycling of water.

Finding the right location was crucial for an envisioned energy complex. It needed to be a location with sufficient water supply, with suitable ground conditions, without earthquake or flood dangers. In addition, the complex needed to be within reasonable distance towards a (potential) industrial settlement to provide this population centre with electricity. Safe and ample water supply had to be considered during site selection and was one of the essential criteria for their construction. If there was not enough water, the complex could not be built.

A leading institute for the creation of energy complexes was Gidroproekt (Hydroproject). As the name suggests, Gidroproekt was a Soviet hydraulic research, design and construction agency. By joining its hydraulic expertise with newly introduced nuclear engineering, this institute was the very place where knowledge transfer between these two prestigious engineering communities took place. Here, the water-focused perspective prevailed and embedded nuclear technology into hydro-ameliorated aquatic systems. It promised prestige as well as quick results – and Gidroproekt readily delivered.

In sum, both in the East and the West, water played a crucial role in the development of nuclear power. In the West, knowledge about water was essential for developing nuclear safety practices. In the East, water was seen as a crucial resource, for powering energy complexes in the struggle for building a Communist state. Nuclear’s reliance on water meant that nuclear power plants and energy complexes were meeting places of different long-standing traditions and communities. Given the large number of water-cooled reactors in the world today, and including those under construction, it is fair to say that this crucial connection is there to stay.

Achim Klüppelberg & Siegfried Evens

Doctoral students at division for History of Science, Technology and the Environment, within the ERC-funded project Nuclear Waters

Project team in Sweden

Project team in Sweden