by Giulia Borsa, Researcher

We are the victims of a planet that is warming and ice caps that are melting, pushing sea levels higher and swamping the land that we have traditionally occupied.

Commodore J.V. Bainimarama (Prime Minister of Fiji)

Because of climate change, many people around the world face serious consequences, including the threat of losing their homes. One of the most serious inhabited areas now under threat is the nation of Fiji. By discussing the case of the Fijian village Vunidogoloa, we can see the tangible effects now facing thousands of communities that are being displaced worldwide as a result of our burning planet. In addition, we can learn about the current best practices of community-based relocation.

The story of climate change, though widespread, is not common, and, in many ways, must still be told. The gases in the earth’s atmosphere regulate our climate. Nevertheless, the vast majority of global transportation systems and industries rely on burning fossil fuels which increases the proportion of some gases in the atmosphere. For instance, agriculture and meat industries release high levels of carbon dioxide and methane. These gases are responsible for trapping ongoing longwave radiation in the climate system. Through such artificial augmentation (by human activity), the natural greenhouse effect becomes stronger and the earth warms. As a result, forests and oceans that have acted as “sinks,” absorbing part of the emissions of greenhouse gases have become “full.” Their capacity to absorb industrial emissions has failed due to various effects such as acidification, warming and pollution. Consequently, climate change now leads to a global warming of the layers of earth, oceans, a change in precipitation patterns, the melting of glaciers, sea level rise, ocean acidification, and frequency of extreme weather, namely storms and heat waves.

One of the locations most impacted by this changing climate are small islands. Regardless of their location, small islands are particularly vulnerable to the effects of climate change. Due to their limited size, their natural and socio-political resilience to weather natural hazards and external shocks is much lower than other countries, exposing them to greater risks.

Leaving Vunidogoloa

In the case of Fiji, the country is witnessing the worst impacts of climate change such as sea level rise, warmer temperatures, ocean acidification and intensified ‘El Niño’ patterns (interaction of the oceans and atmosphere modifying temperatures). This intensification of weather events due to climate change implies higher risks of drought and floods, endangering drinking water resources. Indeed, due to coastal floods, the incoming saltwater has destroyed crops, augmented water- and food-borne diseases and endangered the nation’s coral reefs. Such an impact on the ecology of the islands and health of its people is further exacerbated by extreme weather events, such as tropical cyclones and heat waves, that have caused injuries and illness namely vector- and water-borne diseases as well as augmented the risk of malaria and dengue fever.

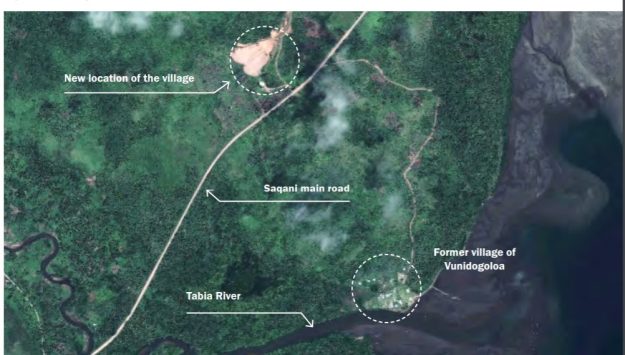

Vunidogoloa was the first Fijian village to experience the impacts of climate change. Located on the island of Vanua Levu, the village was composed of 26 houses in which 32 families lived. Starting as early as 2006, floods and erosion caused by both sea-level rise and increased rains, started to become stronger, reaching homes and destroying crops. The situation was getting worse every day, with water coming in and taking the land away progressively. The mangroves that used to cover the whole coast were absorbed by the sea. Some houses were, in the words of the headman of Vunidogoloa, “like ships in the water.” The community feared for their children, suffered from agony and experienced the worst consequences on their land: crops destroyed, scarcity of drinking water resources, fewer yields from fishing and endangered access to roads. It ceased to be the idyllic spot it used to be decades before.

In order to manage the risks and impacts of climate change, the village undertook several adaptation action programs. Several of the homes most affected early on were moved using Vunidogoloa’s own resources. They also petitioned the Japanese government, who funded the construction of a seawall to protect from sea-level rise and inundations. However, this ended up being more harmful afterwards. Water that breached the seawall could not flow back unobstructed to the sea; the seawall actually exacerbated flooding.

Progressively, the severity of floods and erosion made relocation the only hope for the citizens of Vunidogoloa. Considered a last resort, relocating the village seemed their only remaining hope. Hence, the villagers asked the help of their government in 2006. Unfortunately, steps towards a relocation plan were not taken until 2012, when the National Summit for Building Resilience to Climate Change was held. From the beginning, the relocation process was driven by equality concerns and based on consultation, consensus and participative decision-making process. As a result, 30 identical houses were built in accordance with the villagers’ choices, which treated all residents equally. Counting with the works of qualified volunteers provided by ILO (Edwards, 2012), the own villagers and unemployed people, a more sustainable concept of residences was promoted. This included the insertion of solar panels and natural system of draining water. In 2014, the relocation process started, transferring the villagers from the coast to a nearby location (also in Cakaudrove Province) further inland and at higher altitude. The residents named their new home, Kenani, from the biblical word Canaan, meaning promised land.

Adapting to Kenani

But the move to the promised land is not all honey and locusts. Relocation is difficult, with significant economic, social and psychological impacts on those making this journey. For instance, relocating a village is expensive. In the case of Vunilodogoa, the move cost a total of 980,000 USD. The Fijian government paid approx. 740,000 USD, and the community paid out approx. 240,000 USD in the value of the logs used to construct the new houses and taken from Vunidogoloa. For the villagers, relocation was also described as “the saddest event of their lives.” Fijians consider their land as part of their identity, as something belonging to their ancestors and in need of care to ensure its prosperity as a dwelling space for future generations. To lose it constitutes a physical, emotional, and psychological ordeal. Leaving the village led the villagers to make the traumatic decision to exhume the remains of their ancestors. Luckily, the local church provided the transfer of the burial site. Now, the cemetery is closer and more convenient according to one elder villager.

In addition, resident diets and food practices changed with the move. They started planting bananas and pineapples tops provided by International Labour Organization. Additionally, as direct fishing from the ocean was no longer feasible, a shift to fish ponds was made, with the contribution of the Ministry of Fisheries who provided the fish and prawns. In addition, the relocation project aimed to “improve” the lifestyle of the villagers, providing them with separated kitchens, bathrooms and individual taps for washing. Likewise, access to the hospital is not any longer a challenge thanks to the village’s proximity to the main road.

Such changes affected, in particular, women, the elderly, and children. Regarding women, moving impacted them negatively at the outset. Whereas they used to fish daily in Vunidogoloa, men used to work in the farms. However, in Kenani, the sea is not nearby the village, which means that going fishing would involve an extended period of time. Thus, their husbands—decision-makers in their patriarchal society—would not allow them to go fishing but rather focus on household labor. This made women more dependent on their husbands to subsist in an early stage. However, as fish farms started to be installed, women were able to resume fishing activities. Moreover, having individual taps for washing allowed women to spend less time waiting at the community tap and socialize with other women or recreational activities such as mat weaving. Likewise, many rural women received empowerment training in solar engineering provided by a female villager who completed a UN Women-funded programme on solar engineering. For the elderly, the new location reduced their movement due to its higher position and terrain. Their social daily activities, walking, going to the church, or visiting relatives, were reduced. Children are now able to attend school daily, as they no longer have to cross a tidal river (dangerous under bad weather conditions) and can use the local bus to get to school instead.

Final Thoughts

In the National Climate Change Policy (NCCP) approved in 2012 by the Fijian Government, the report mentions a need for post-relocation monitoring and consultation to identify any long-term issues for relocated or host communities. In an interview, the climate change unit of the ministry of foreign affairs and international co-operation responded that this was to ensure the sustainability of the relocation process for the affected community. However, it remains unclear the consideration of the psychological or social impacts of relocation in such a monitoring program.

Nevertheless, in many respects, relocation has been a temporary lifesaver for this community that—although having contributed very little to climate change—has been severely affected by it. As noted earlier, this process involves losses and damages; yet, overall, the sources I’ve analyzed outline its success. Some former villagers of Vunigodoloa have even defined their lives as “easier” than before. It seems that women were impacted mostly at the beginning of the relocation process. Still, in a source from 2017, the situation of the elderly did not seem to be improved. Hopefully, we all can learn from Vunidogoloa a lesson of endurance. Moreover, may it serve as a call for action to industrialized countries and future decision-makers the timeliness and urgency for addressing the loss, damage and traumas that come as a result from relocating due to climate change.

Further materials

- Audiovisual materials

- “Escaping the waves: a Fijian Village relocates” [2015], The Sydney Morning Herald

- Books

- Charan, D; Kaur, M; Singh, P, “Customary Land and Climate Change Induced Relocation—A Case Study of Vunidogoloa Village, Vanua Levu, Fiji” in Leal, W, “Climate Change Adaptation in Pacific Countries” [2017].

- Press

- Bertana, A “How a Community in Fiji Relocated to Adapt to Climate Change” [2017].

- Meakins, B. “An Inside Look at the One of the First Villages Forced to Relocate Due to Climate Change” [2017], Alternet.

- Rubeli, E, “Escaping the waves: a Fijian Village relocates” [2015], The Sydney Morning Herald.

- Sorowale, S, “Climate Change and Relocation in Fiji” [2012]

Author Bio:

Giulia Borsa is an International Human Rights jurist. Giulia has been working as a postgraduate researcher for the past two years, and this blog entry is the outcome of her collaboration with the project CLISEL – a Coordination and support action of Horizon 2020. She was one of the participant to the Environmental Humanities Training School that the KTH EHL, organised in Naples in December 2018 on “Loss, Damage, and Mobility in the context of Climate Change.” She holds a bachelor’s degree in law from the University Autonoma of Barcelona and an LLM in International Human Rights Law from Oxford Brookes, with a dissertation written on climate change related displacement. She has also been coordinating the division on Climate Change and Human Rights of the International Organization for Least Developed Countries (IOLDCs) in Geneva, and she is currently working at Ecovadis. She has won several awards, including the Ideas that Change the World Competition in Oxford in 2018.

I programmet har vi Saskia Sassen, sociolog och professor vid Columbia University, speciellt inbjuden som hedersgäst för att presentera Fredrik Gertténs omtalade dokumentär Push, där hon även själv medverkar. I en efterföljande panel samtalar Saskia tillsammans med Erik Stenberg, arkitekt och lektor KTH och Marco Armiero, lektor och miljöhistoriker KTH om städers gentrifiering och konsekvenserna av detta. Samtalet modereras av Miyase Christensen, professor i media och kommunikation vid Stockholms universitet.

I programmet har vi Saskia Sassen, sociolog och professor vid Columbia University, speciellt inbjuden som hedersgäst för att presentera Fredrik Gertténs omtalade dokumentär Push, där hon även själv medverkar. I en efterföljande panel samtalar Saskia tillsammans med Erik Stenberg, arkitekt och lektor KTH och Marco Armiero, lektor och miljöhistoriker KTH om städers gentrifiering och konsekvenserna av detta. Samtalet modereras av Miyase Christensen, professor i media och kommunikation vid Stockholms universitet.

Do dogs dream? What do those dreams tell about us? Why should it matter to us? And who is “us”? Those are but some of the questions that Eduardo Koch learnt to address from the Runa Puma people in Avila, on East Ecuador Amazonia. “How Forests Think” is a book about finding back the common ground; a common ground which is both material and spiritual, human and animal; a common ground that belongs to the ones who are still alive as well as to the ones who are now dead. The book, which is the result of the many years spent by the South American anthropologist together with the Runa people, can be ascribed as an environmental humanities work, though the author does not state it. Nonetheless, in the introduction the author writes that one of his goals is “neither to do away with the human nor to re-inscribe it, but to open it”. What does he mean with opening “the human”? And how does that relate with dogs’ dreams? The point he wants to stress is that both humans and dogs are in a relationship, as all the living beings do. To criticize the Cartesian divide and the human exceptionalism which spurs from it means to change western scholars point of view and to start seeing as a runa puma – a were-jaguar – which is both human and non-human, dead and alive, corporeal and transcorporeal. All Living beings are signs – according to Koch, which gets this from the American philosopher Charles Pierce, the founder of semiotics –, which means that they are all ongoing relational process of signification. From this ontologically egalitarian standpoint, Koch elaborates a phenomenology of life that is built upon the infinite relationships and encounters that unite human with all other living beings. Those are all selves in that they interpret and react to any socio-environmental interaction they participate to and co-produce. The co-production of signifying relations of which Koch talks about can be framed as well as an ecological network that is the result of the bodily and affective trajectories of all the living beings. Those trajectories are in Ingoldian terms the “waypoints” of the semiotic process that is life.

Do dogs dream? What do those dreams tell about us? Why should it matter to us? And who is “us”? Those are but some of the questions that Eduardo Koch learnt to address from the Runa Puma people in Avila, on East Ecuador Amazonia. “How Forests Think” is a book about finding back the common ground; a common ground which is both material and spiritual, human and animal; a common ground that belongs to the ones who are still alive as well as to the ones who are now dead. The book, which is the result of the many years spent by the South American anthropologist together with the Runa people, can be ascribed as an environmental humanities work, though the author does not state it. Nonetheless, in the introduction the author writes that one of his goals is “neither to do away with the human nor to re-inscribe it, but to open it”. What does he mean with opening “the human”? And how does that relate with dogs’ dreams? The point he wants to stress is that both humans and dogs are in a relationship, as all the living beings do. To criticize the Cartesian divide and the human exceptionalism which spurs from it means to change western scholars point of view and to start seeing as a runa puma – a were-jaguar – which is both human and non-human, dead and alive, corporeal and transcorporeal. All Living beings are signs – according to Koch, which gets this from the American philosopher Charles Pierce, the founder of semiotics –, which means that they are all ongoing relational process of signification. From this ontologically egalitarian standpoint, Koch elaborates a phenomenology of life that is built upon the infinite relationships and encounters that unite human with all other living beings. Those are all selves in that they interpret and react to any socio-environmental interaction they participate to and co-produce. The co-production of signifying relations of which Koch talks about can be framed as well as an ecological network that is the result of the bodily and affective trajectories of all the living beings. Those trajectories are in Ingoldian terms the “waypoints” of the semiotic process that is life.