Make the Baltic Sea happy again

“I have met both goodtemplars and tee-totallers, but no one has refused the traditional fish schnapps. That’s the most absurd thing I’ve heard in my entire life; to skip the fish schnapps. When fish is the only food you get here in the archipelago!”

The quote above is from the book Roslagsberättelser by Swedish author and artist Albert Engström, published in 1942. Eighty years ago, fish was the only food available in the Baltic Sea archipelago. Today, the only fish to be found in the archipelago comes by refrigerated truck from Gothenburg. Engström worried that his beloved “rospiggar”, his fishermen and skippers, customs officers and smugglers, would disappear from the archipelago. But the fish disappearing, that was probably unimaginable eighty years ago.

We are many who can share childhood memories from the coast, from fishing excursions and sailing trips. We all agree that there has been a sharp deterioration in our marine ecosystems during our own lifetime. So the question is; can we live sustainably around the Baltic Sea?

The Baltic Sea is special. Basically, it consists of a depression in the Phenobaltic bedrock shield that arose 400 million years ago when Scandinavia collided with Greenland. But what we call the Baltic Sea today is much younger, just a few thousand years old. When the ice sheet began to melt about 14,000 years ago, the Baltic Sea first became a lake full of meltwater. Then, when the surface of the world’s oceans rose, it became a saltwater bay. Due to post-glacial landrise, the connection with the Oceans narrowed and the Baltic Sea has been brackish for the past 3,000 years. It is thus a very young – therefore fragile – ecosystem. A couple of thousand years is not much for species to adapt and thrive.

One species that thrives is homo sapiens. Today, we are around 85 million people in the Baltic Sea catchment area. We live in 14 countries and speak different languages. We have different economics and policies, and different relations to the Baltic Sea. Of course, collaborating can be difficult and the Baltic Sea was for a long time a perfect example of the “tragedy of the commons”, with over-fishing and garbage dumping. We now also know that climate change will increase runoff and thus inflow of harmful substances, while development pressure increases along coastal areas.

What matters is what we can do about it. KTH has started the Baltic Tech Initiative to seek concrete and scalable solutions to three key challenges.

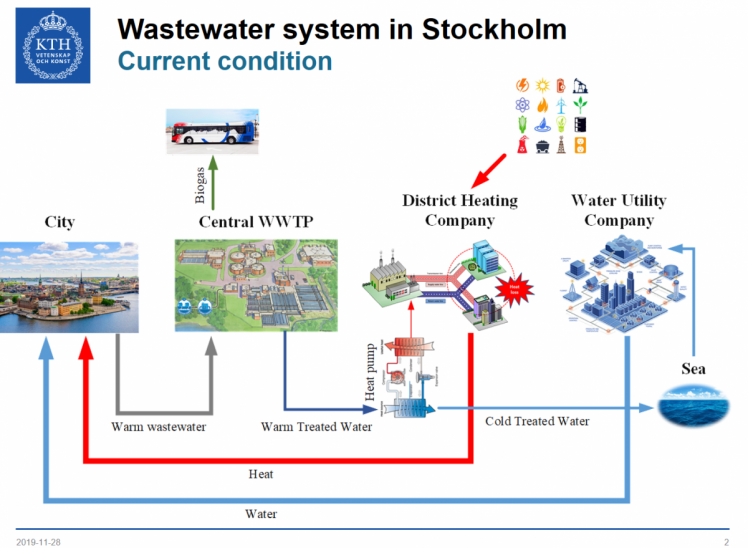

- Reduce the impact of humans. For example, with constructed wetlands we can reduce the load from watercourses, where 95% of the phosphorus supply and 70% of the nitrogen today come. The electrification of transport by sea is another area KTH wants to speed up.

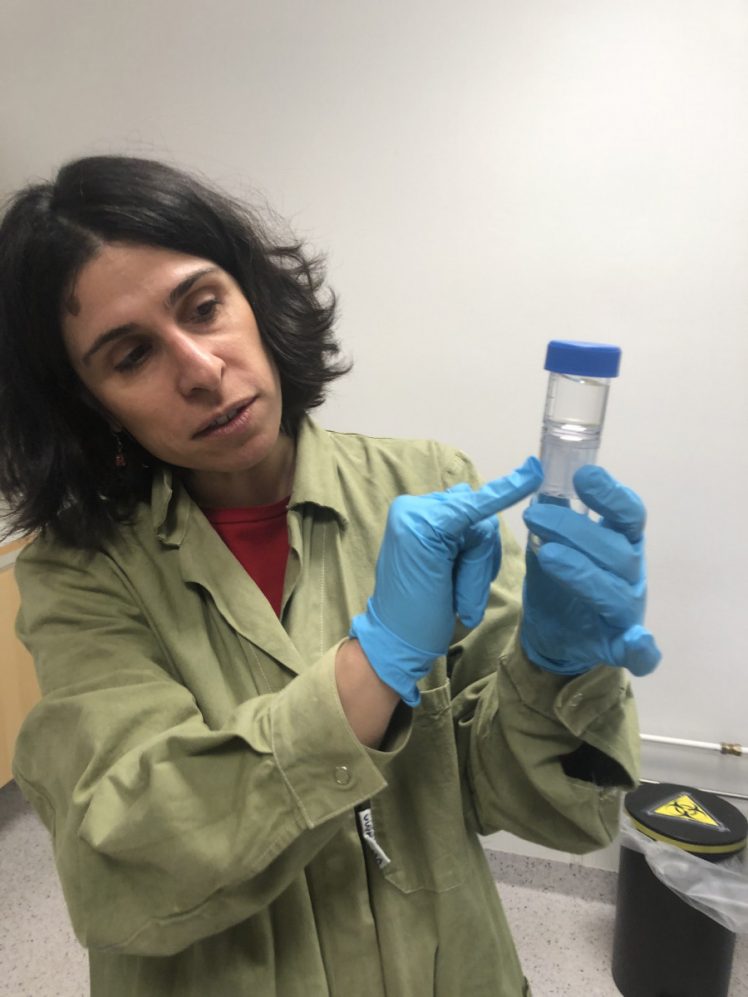

- Deal with old environmental sins. The amount of nutrient inflow has decreased sharply since the 1980s, but large amounts of phosphorus remain in the sediments. Phosphorus is a finite resource needed for food production and KTH is now testing whether it is possible to recover phosphorus from sediments in the Baltic Sea and utilize it on land again.

- A data revolution in the oceans. We are on the doorstep of a new era. For thousands of years we have managed the oceans in exactly the same way we managed our terrestrial lands as hunters and gatherers. We have enjoyed a predator’s life at the top of the food chain. If we are to manage the oceans sustainably, and cultivate our food, energy and our industrial raw materials, then knowledge is going to be absolutely crucial. A data revolution in the oceans is around the corner and the instrumentation of marine environments has started. The sea is our next space race, and we do not want to make that journey blindfolded.

KTH is just one of many actors and by collaborating with others we can achieve more. KTH can not do everything. But we will do everything we can. Do you want to join us on that voyage?

David Nilsson

Director, WaterCentre@KTH

Scientific Coordinator of KTH Baltic Tech Initiative

This text is an edited and shortened version of David Nilsson’s speech at the KTH Baltic Tech launch on 1 December, 2021.