Research aims at cutting steel emissions

The steel industry, source of some of the highest emissions of carbon dioxide (CO2,) is on the verge of a green revolution. Together with three industrial giants, KTH is developing technology to make Swedish steelmaking fossil fuel free.

Swedish steel producer SSAB accounts for around 10 percent of CO2 emissions in Sweden. On a global scale the steel industry accounts for some 7 percent. Meanwhile, the demand for steel shows no signs of slowing – rather, it’s the opposite.

“If we are going to achieve our climate targets, we cannot continue producing steel in the way we do today,” says Johan Martinsson of SSAB, who is also employed as a researcher at the Institution for Materials Science and Engineering at KTH.

“We need to do something drastic.”

The project, initiated by SSAB, Vattenfall and LKAB, is called Hydrogen Breakthrough Ironmaking Technology (HYBRIT) and aims to manufacture steel using hydrogen.

Around 90 percent of the CO2 emissions from steel production can be explained by a technology that has been around for 1,000 years. Iron ore is transformed into steel using blast furnaces that extract iron from the ore at high temperature with the addition of coal, a fossil fuel. The iron ore becomes sponge iron – and the residual product is CO2.

Fossil fuel-free process

That’s about to change, Martinsson says. “The most practical way is to replace the coal that is used today with hydrogen. The residual product will then be water instead of CO2.”

Producing hydrogen is energy intensive, but this too will be done with the help of fossil fuel-free sources.

The HYBRIT project is divided into six research areas, of which KTH is involved in three: the smelting of iron ore with the aid of hydrogen, the actual steel production process, and how the necessary hydrogen is to be produced and stored.

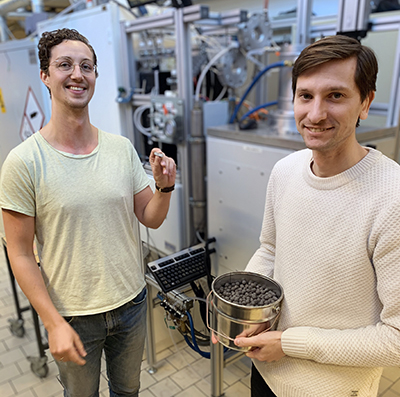

Martinsson’s project team is based in a lab plastered with yellow warning signs, such as skull-and-crossbones symbols that remind users of the operational dangers. Here, they’ve built a furnace in mini format which reaches temperatures of 1,100C as it reduces iron ore to sponge iron with the help of hydrogen.

Doctoral student Joar Huss uses the furnace, dubbed “Baby Blue”, to smelt the iron sponge, and he purifies it by removing phosphorus and sulphur. Martinsson is also working on a part of this purification process which focuses on the porous mass of iron and slag called “bloom”.

Green profile

Now in the process of construction in Luleå is a new kind of shaft furnace into which hydrogen is blown, which would replace the blast furnaces. The plant should be completed this summer.

“It’s no small thing, a 50-metre construction is concealed inside, and it should be able to produce iron sponge at the rate of 1 tonne per hour,” Martinsson says.

The first research project from KTH should be completed next year, but Martinsson and Huss are looking forward to similar cooperative projects.

“HYBRIT will ensure that this type of knowledge remains at KTH. There is an express aim to develop people within this area and inspire young people to study materials science,” Huss says.

By 2026, the first demonstration plant should be up and running and then the first fossil fuel-free steel should be ready to leave the SSAB gates.

There has been enormous interest from potential customers and, according to Martinsson, many industries want both fossil free fuels and materials to gain a green profile.

Anna Gullers/Christer Gummeson