Better knowledge of dangerous substances can prevent life-long allergies

An estimated 4,300 common chemicals in society can trigger an allergic reaction on contact.

“Chemists and dermatologists need to work together to tackle the growing problem with allergies,” says Yolanda Hedberg, a researcher at the Department of Chemistry and docent at KTH.

A contact allergy is a life-long disease. Once your skin has reacted to a molecule, your body remembers this for the rest of your life.

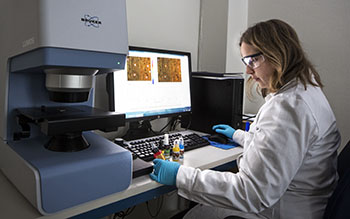

KTH researcher

Yolanda Hedberg

has contributed to a chemically refined diagnostic method for skin allergies, in cooperation with Region Stockholm.

“We have investigated allergic reactions caused by everyday products such as cosmetics, implant materials, clothes and shoes,” she explains.

“Diagnoses are determined via tests using so-called patch test chambers, that we have analysed and refined at the Occupational and Environmental Medicine Centre

Centrum för Arbets- och Miljömedicin

.

Together with research colleagues, Hedberg has also been supporting the European Chemicals Agency for the last couple of years in lobbying for legislation to protect consumers against harmful substances in products.

Despite measures such as the Registration, Evaluation, Authorisation and Restriction of Chemicals in the EU,

REACH

, there has been an explosive growth in allergy cases in society.

“It's difficult to entirely avoid allergy invoking substances today, they are found almost everywhere,” she says.

Demanding work to find the cause of a contact allergy

According to Hedberg, an estimated 35 percent of all women and 17 percent of all men currently have developed a nickel allergy.

“Nickel allergy is the commonest form of contact allergy. If you have it, you can get dermatitis from contact with the metal in objects such as glasses, watches, belts, tools and keys. And we must not forget that a further 4,300 chemicals in our society can trigger contact allergies …

A contact allergy always arises where the substance has been in contact with the skin, but often only a couple of days or even weeks later. This means it can take a bit of detective work to work out what has caused the allergy.

“We need to raise public awareness of what a delayed contact allergy actually means. Many people think they have suffered a direct allergy when they get a skin rash, but in the case of contact allergies, the reaction can be delayed several weeks,” says Hedberg.

“My best advice is always to perform allergy tests as recommended on the packaging before any beauty treatment such as hair colouring, piercing, false nails, false eyelashes, face masks or getting tattoos. You also need to wait at least a couple of days to see whether you have a possible allergy. Serious allergic reactions can be life threatening in the worst case.”

She also stresses that it can be difficult for doctors and dentists to determine if it is a case of a delayed contact allergy from an implant, for example.

“That’s why closer cooperation is needed between care providers and chemists. As researchers, we are already helping many sectors when it comes to occupational allergies today, such as preventing chromium allergy that can be caused by cement and work gloves. Not many people are aware that leather often contains chromium, and shoes can also cause severe allergic discomfort,” Hedberg explains.

The beauty industry is particularly vulnerable to powerful allergy invoking substances, and the problem is especially common in hairdressing salons and nail bars.

“Everyone who gets a rash from substances they use on a daily basis as part of their job, must make sure they take protective measures in good time, as once you have developed a contact allergy, you can be forced to change your job.”

Hedberg is currently supervising a Vinnova financed student project on substances in tattoo inks that are hazardous to health, that is expected to be completed in May 2020.

Katarina Ahlfort

Photo: Håkan Lindgren