Dressed for occupational health

In the workplace of the future, the risk of injury, stress and sick leave can be reduced. That is the hope of two KTH researchers who propose an interdisciplinary method to take the temperature of the workplace with the help of sensors in our clothing.

In the intersection of technology, medicine and ergonomics, professors Jörgen Eklund and Kaj Lindecrantz are working with new methods that could save money and reduce suffering.

Clearly the labor market will change dramatically in the coming decades. Among other things, it is expected that half of all jobs today will be automated or digitalized and disappear. But how will that transformation affect the workplace for those in 2035 who work essentially as they do now?

"There are different ways to look at it," Eklund says. "It's not news that jobs are being automated with the help of technology. That's been happening since the 1800s when looms were automated. Robots have for example been used in manufacturing for heavy and dangerous tasks in closed systems."

"People will work increasingly together with robots in the future, " he says. "That means that the risk for accidents is greater, but it also creates opportunities for challenging work in which technicians service and fine-tune their colleagues."

Eklund points out that by the 1970s, sociotechnical theory became more prevalent as people who shared the assembly line with robots began feeling more isolated. Production lines were then realigned as semi-circles, with the operators on the inside. The configuration enabled them to have better contact with each other.

"The desensitizing of people and how to set up machines or robots will likely become an important issue in the future. Robots themselves are neither good nor bad, but how they are used is crucial," he says.

Lindecrantz says it is difficult to predict the risks inherent in those residual jobs that remain 20 years from now. "When for example, refuse collectors began using mechanical lifts on the back of the rubbish truck, they no longer were required to do heavy lifting, but instead increased the stress on their shoulders with the joystick they had to use."

A good work environment generates good quality or service, many studies show. Eklund and Lindecrantz are convinced that good workplaces are an important competitive advantage in the global economy. The work environment also is a significant factor in discussions about raising the age of retirement.

"The work environment deserves continuous attention; it is not something that we should consider a luxury to address," Lindecrantz says.

Work environment issues are not as hot as they were 20 years ago. KTH's work environment knowledge course used to be mandatory, but today it's an elective. Meanwhile workplace injury reports and sick time have increased during the last five years in Sweden.

"Silicosis, for example, was nearly eliminated 10 years ago, but now it's making a comeback," Eklund says.

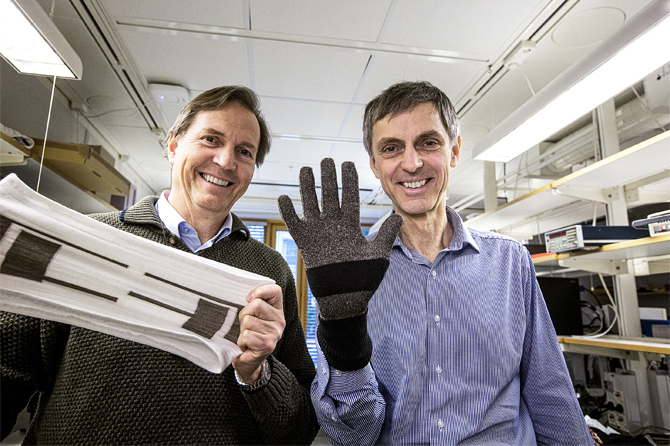

Lindecrantz produces a box holding an example of gear that could one day be used to promote sustainable workplace health through diagnostics.

With sensors and electrodes in our work clothing, physiological indicators, such as heart rate, pulse and sweat, can be monitored. In addition to providing information about physical affects of the work environment, the data can be analyzed to understand the psychological impact, in real time rather than when it's too late.

Lindacrantz has been involved in the development of the kind of fabric-based electrodes that are becoming widely used in athletics, where for example they are used to measure heart rate. Such electrodes also are used in medicine. Integrated EEG sensors can be found in caps that babies wear in on their heads while lying in incubators; and similar sensors are used to transmit information directly to the hospital while heart attack victims are being transported via ambulance.

With such data, employers could determine whether jobs are unsuitable or if workers are being overloaded, which could in turn increase the inclination to change the work environment, he says.

"Bad workplaces ultimately cost more," he says. "When you can visualize the measurements and pinpoint the problem, which perhaps you cannot see with naked eye, then the connection becomes clearer."

In the future, employees can be monitored and analyzed to the smallest sweat drop and movement. But what about privacy?

"That's a question for policymakers. Anything can be abused, so it's important to know what you're asking for."

Lindecrantz uses a harness racer as an example. Suppose the driver wanted to attach sensors to the horse so he'd know whether the horse is tired or simply lazy, he says. With that knowledge the driver intends to push the horse harder if sensors indicate it is mere laziness that is slowing the horse down.

"The difference is that our system will prevent work injuries and health problems, not increase the demand."

Jill Klackenberg