Tracking the spread of microplastics

Microplastics are spread by currents and waves across the world's oceans, threatening both ecosystems and human health. In ongoing research, KTH researcher is developing a new modelling tool to track how plastic particles move and where they accumulate.

“Microplastic pollution in the marine environment is one of our biggest environmental challenges. It can affect critical ocean currents such as the Gulf Stream, alter ice melt and impair plankton behaviour and survival,” says Bijan Dargahi , Associate Professor of Hydraulic Engineering and visiting researcher at the Department of Sustainable Development, Environmental Science and Technology at KTH.

Microplastics in the oceans come from many sources – everything from households and sewage treatment plants to industrial emissions. The particles can float long distances with the ocean currents, accumulate in large concentrations or sink to the bottom.

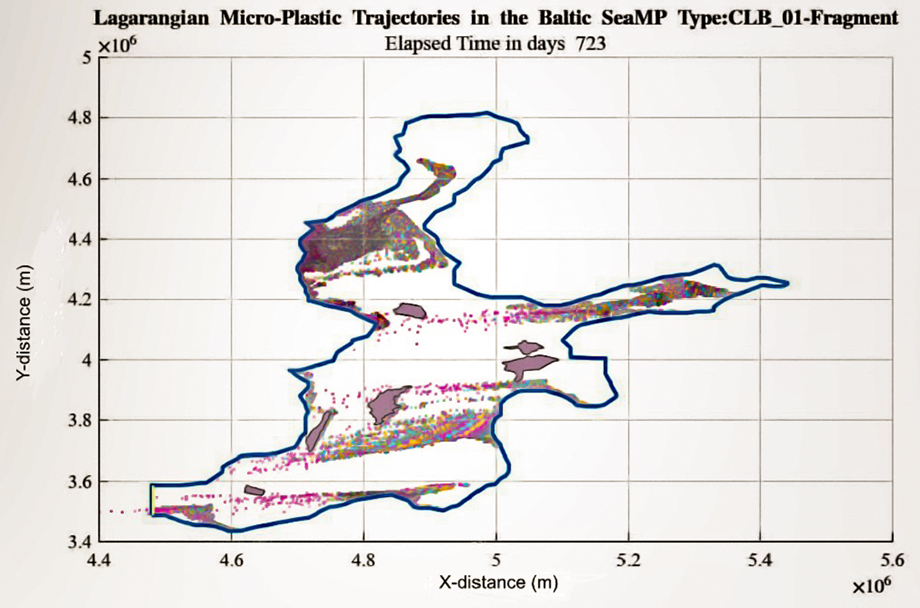

To better understand these movement patterns, Dargahi has developed a modelling tool that tracks each individual particle and how it is affected by water movements and wave forces.

First step

The research has not yet been published, but is based on his previously published and acclaimed studies on similar modelling tools.

“Understanding the physics behind how plastic is transported in water is the first step in reducing or controlling microplastic pollution,” he says.

Using data on currents, waves and temperature, the model can simulate what happens to microplastics in the sea over time. It takes into account that plastic can be washed ashore, covered by organisms, broken down, split into smaller pieces, sink to the bottom or be swirled up again.

“All the forces that affect microplastics are included in the model. This makes it possible to track how individual particles actually move, unlike previous research, which has often focused on measuring microplastic levels rather than their path through the sea”.

Protect the Baltic Sea

The tool is specially adapted for the Baltic Sea, where the aim is to protect a unique and highly sensitive marine environment. The goal is to be able to map how microplastics spread along the coasts, around islands and on the seabed – and how much floats and how much sinks into deeper water.

At the same time, Dargahi emphasises that technical solutions for cleaning the sea, such as filtering, breaking down or binding microplastics, are only of limited use.

“It is certainly impossible to predict how useful technological developments will be. But cleaning the oceans of microplastics on a large scale is extremely difficult. The most important thing is to reduce the amount of plastic entering the oceans in the first place,” he says.

The aim is for the research to contribute to increased awareness and stronger commitment, both among the general public and decision-makers.

“Plastic must be prevented from ending up in the sea. This requires strong policies and measures that stop pollution at source”.

Text: Christer Gummeson ( gummeson@kth.se )